We share first impressions of the Impossible Conversations exhibit and ask: Are you a Prada or a Schiap?

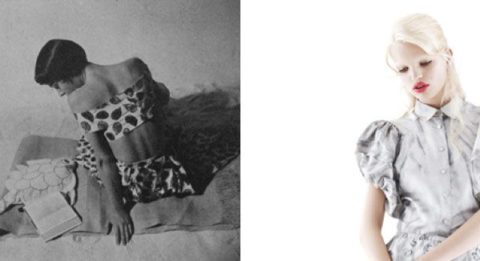

Last night on livestream, when one Met Gala-goer after another swore they were only really wearing that $50,000 look to the Oscars of fashion so they could sneak-peek “Impossible Conversations,” I almost believed them. The Metropolitan Museum’s daring pairing of a designer exhibit is that good: Schiaparelli, meet Prada; Prada, meet Schiaparelli. Hello, two most seminal fashion designers who also happen to be badass women. Themes of beauty, vulgarity, femininity, labour and play are explored deftly, with sometimes-ingenious curation and a script that tells you just enough to make you want to go to the library. The similarities between the two designers, whose work was separated by a half-century, are remarkable. Their differences are fascinating.

Baz Luhrmann‘s film, which pairs a real live Miuccia with a startling facsimile of Schiap, played by Judy Davis, plays those imagined “conversations” in segments throughout. The looped aphorisms bring to mind another iconoclastic fashion ghost, Diana Vreeland, whom you might call the Phantom of the Met (it was she who introduced such exhibits to the Costume Institute, and curated them for 12 years). I imagine that Vreeland, with her contradictory ideas of chic, could have mediated their disputes about whether fashion is art, for example. The rest of us will have to pick sides.

And so, welcome to Impossible Choices, in which you decide whether you’re Team Prada or Team Schiaparelli. Everybody wins! Bonus: the answers reveal secrets about the exhibit, which runs at the Met from May 10 to August 19.

Time to make some impossible choices »

QUESTIONS:

1. Speaking of the Met Gala, you’re invited—but you can’t afford a ball gown and you’re not bloody Cinderella. What big statement-type accessory do you buy?

a) An opulent, one-of-a-kind necklace to keep all eyes hovering near your seductive face.

b) Standout shoes, because even the wildest flights of fantasy must stay grounded somewhere.

2. What’s your favourite colour?

a) Brown, mostly because it’s nobody else’s favourite colour.

b) How could one possibly choose? But in general, the brighter the better.

3. Beauty ideals are best challenged through _________.

a) Subversion.

b) Perversion.

4. How do we understand ourselves?

a) By understanding our dreams.

b) By understanding our limitations.

5. Birds or insects?

a) Insects, for their delicacy and strange powers.

b) Birds, for their beautiful colours.

6. Would you rather wear…

a) An evening dress to your day job?

b) Or a trouser suit to the fanciest party?

7. Is fashion art?

a) Yes, it absolutely should be!

b) No! Who cares?

ANSWERS:

1. a) Schiaparelli designed for women in 1930s Parisian “cafe society,” which meant they were always sitting, and needed to look best from the neck up. Jewels, hats: these defined her metier.

b) In Miuccia’s world, the skirt rules: she works to embellish and protect the nether regions, site of sex and birth and femininity. But if you’re looking at a knee-length hemline, you’re also looking at the feet, and Prada shoes have become, over the years, increasingly superlative statements on decoration and desire.

2. a) Prada has long said that she wants to make “ugly” desirable. Hence, her eternal return to brown, the colour of mud and UPS men.

b) “Colour gives me ecstatic pleasure,” said Schiaparelli, whose most singular legacy is still the coinage of pure, untouchable “shocking pink.”

3. a) Schiaparelli believed fully in her power to shock, deploying surrealist tricks like trompe-l’oeil to fool the eye and disconcert the mind. Her infamous shoe-as-hat, or her unnerving skeleton dress, are lasting examples. A radical feminist, she sought to subvert glamour by doing it better, but also stranger, than anybody.

b) In the oversaturated and globalized marketplace, it is nearly impossible to shock anymore—and in fashion, this necessarily visual medium, what haven’t we seen? Instead, Prada’s clothes take feminine tropes and pervert them. The best example is her Fall 2008 lace collection, sadly underrepresented in the Met show, which looks all at once Catholic and bridal and sinister and sexy.

4. a) Like her surrealist cohorts, Schiap was a committed dreamer. “At moments of restriction,” she said, “fantasy alone can lift people above dreariness.”

b) Prada’s design ethos is firmly rooted in the way we live and move in the physical world. This is her radicalism: that everything a woman wears should be of use.

5. a) Schiaparelli’s famous insect necklace, from the 1938 “pagan” collection, epitomizes her sweet and macabre surrealism.

b) Prada finds absolute beauty in the animal world and says birds have more beautiful colours even than flowers.

6. a) There is an ivory silk velvet gown, circa 1936, that transcends Schiaparelli’s deviant fixations and stands alone as the simplest, and possibly most beautiful, piece in the show. Although she considered herself an artist and derided others, namely Coco Chanel, as “dressmakers,” she too could cut a mean evening gown. “I love to make women slim and elegant,” she said, referencing the Regency period of dress.

b) “I was not able to do a single beautiful evening dress in my life,” says Prada in the “Classical Body” video http://metmuseum.org/metmedia/video/collections/curatorial-departments/ci/the-classical-body. She claims she is not against eveningwear, but she is “against the cliche of beauty,” which makes designing eveningwear for Amazons a little hypocritical.

7. a) At last, we come to the crux. Is fashion art? Schiaparelli—and Salvador Dali, her longtime collaborator—answered the question definitively, and believed fully the yes that resounds through the Met exhibit.

b) Prada, meanwhile, makes the question irrelevant. “Dress designing is creative,” she says, “but it is not an art. We have less creative freedom than artists.” She gives herself even less freedom, perhaps, by sticking rigorously to certain themes, to certain requirements: she makes nothing unwearable, nothing for its own sake. “But to be honest, whether fashion is art or whether even art is art doesn’t really interest me. Maybe nothing is art. Who cares!”

Where Schiaparelli’s work was patently imaginative, Prada’s is often purely deconstructive, achieving its power not through object-status, but through the relation of the objects to our bodies, genders and ways of living. You can see that Prada, a feminist and a genius, is in debt to Schiaparelli. But mistaking some of their visual and thematic similarities for a kinship would be a pretty gross error. They are rivals across time; they form, through their opposing convictions, the dialectic fashioning of female costume.

Or, put less fancily, they’re the Beatles and the Rolling Stones. You don’t have to choose, but you do have to understand the difference.