Everything You Need to Know About PCOS

Like, what exactly *is* it?

Chances are that if you’re a person with ovaries, you’ve heard about Polycystic Ovary Syndrome; more commonly known as PCOS. Maybe it was from your BFF, who’d gone for a check up only to find that she had cysts on her ovaries, maybe it was in the news—like when Dutch model Romee Strijd shared in a May 28 Instagram post that she’s expecting a baby, two years after she was first diagnosed with PCOS. Or maybe it’s a condition that you personally have been diagnosed with. Regardless, there are likely very few degrees of separation between yourself and PCOS—because it’s a pretty common disorder.

“[PCOS] affects one in 10 reproductive-age girls, women or people with ovaries, and it’s across all ethnicities,” says Dr. Yolanda Kirkham, an OBGYN and adolescent gynaecologist.”So, it’s fairly common.” And, Kirkham says, the numbers are actually rising. (More on that later.) But, as scary as it may sound, PCOS is actually a very treatable disorder. So, before you head down that Web MD rabbit hole, read up on what the experts we spoke to have to say about your reproductive and ovarian health.

OK, so what *exactly* is PCOS and what causes it?

First of all, although “polycystic ovary syndrome” sounds daunting, Kirkham stresses that people with ovaries shouldn’t be too stressed about the name itself, especially that PCOS is classified as a “syndrome.” ”The syndrome just means certain things or certain symptoms that we see together as a group,” Kirkham explains. “So women shouldn’t feel they have a ‘disease,’ it’s just that they have this grouping that’s associated with certain factors.”

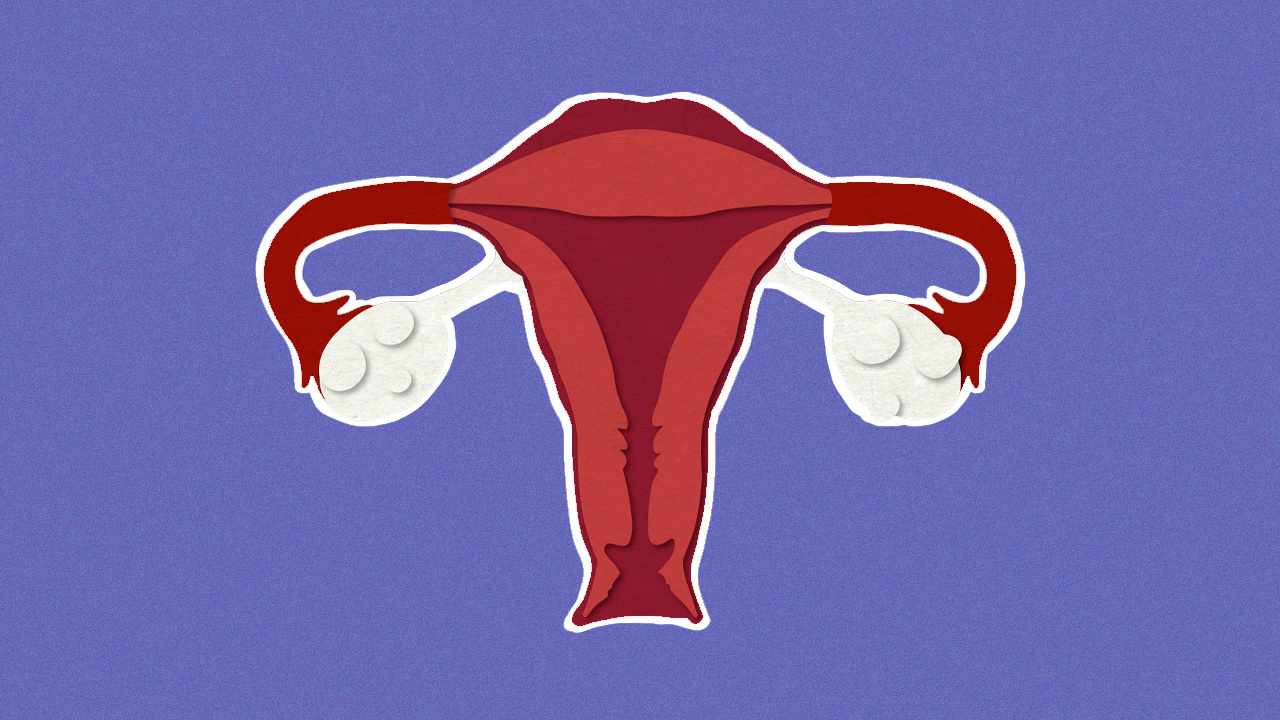

While doctors don’t know *exactly* what causes PCOS (it’s a multifactoral condition, meaning there are many symptoms that can contribute to someone’s diagnosis with PCOS), according to Women’s Health most experts think several contributors—including genetics—play a role. Some of these factors include an imbalance in the reproductive and metabolic hormones. Per Women’s Health, individuals with PCOS may have higher than normal levels of androgens (AKA “male hormones”). While all women have levels of androgens, people with higher levels can face complications. For example, these imbalances can create problems in the ovaries; and with PCOS a person’s eggs may not develop as they should or may not be released during ovulation. “We have thousands of hormones in our body, but it’s in particular the ones that can affect how often we get our periods—as periods are also based on the fluctuations of our hormones—that can cause issues,” Kirkham says. As higher than normal androgen levels can cause missed periods, this can lead to subfertility or the abnormal development of cysts (small, fluid-filled sacs) on the ovaries.

In addition to high androgen levels, people with PCOS may have insulin resistance—meaning that their bodies are unable to break down sugar effectively. This can also lead to downstream consequences for people with PCOS, like diabetes, high cholesterol and uterine cancer. And, it seems to be increasing as instances of obesity increase, Kirkham says.

Is PCOS the same as endometriosis?

While PCOS and endometriosis are often conflated and mistaken for one another, they are *not* the same thing. Per a a report by John Hopkins Medicine, endometriosis refers to a medical condition in which people have irregular development of the tissue that typically lines their uterus (called endometrium). During an individual’s regular menstrual cycle, endometrium tissue builds up inside the uterus and is then shed if the person does not get pregnant. But per the report by John Hopkins, women with endometriosis develop this outside of the uterus, on other reproductive organs inside the person’s pelvis or abdominal cavity. Because the tissue follows the same menstrual cycle of building up and breaking down, but in a misplaced area, this results in “small bleeding inside of the pelvis.” This bleeding then leads to inflammation, swelling and scarring of the regular tissue in the abdominal cavity. Endometriosis can be incredibly painful and is considered one of the three major influences of female infertility, with symptoms running the gamut from pain during sex to excessive menstrual flow and extreme menstrual cramps.

According to Bustle, the misdiagnosis of endometriosis as other medical issues (including PCOS) is due in large part to the fact that many of the symptoms of endometriosis are also present in other conditions. And the conflation of the two conditions can even be made by health professionals, which can lead to misdiagnosis when doctors see cysts on a women’s ovary (something all women have…more on this later) and surmise that the pain they’re experiencing must be a byproduct of PCOS. “Women might show up [in the emergency room] because they have extreme pain and they might have endometriosis, but you can’t see that on an ultrasound,” Kirkham says. “But they happen to have an ovarian cyst at that time because they’re about to release an egg, and then they get diagnosed, [with a Dr. saying] ‘Well you have an ovarian cyst, there’s the problem and that’s why you have pain,’ but it isn’t.”

What are the symptoms of PCOS?

When it comes to determining whether or not you have PCOS, Kirkham says doctors look to the Rotterdam criteria for diagnosis. This criteria mandates two of the three symptoms be present. ”The first one would be infrequent or missing periods,” Kirkham says of one possible PCOS indicator (this means fewer than eight periods in a year). “This is probably what usually would bring a woman or a person with ovaries to a doctor’s office, is that they start skipping their periods or they may be a teenager who is 15 or 16 and has never had a period, or anybody of reproductive age who starts missing three periods in a row.” The second symptom is acne or unwanted hair (otherwise known as hyperandrogenism or high male hormones); meaning that you may have unusual hair on your chin, side of the face, chest, back or stomach. “And the third [symptom],” Kirkham says, “is polycystic-looking ovaries on an ultrasound.”

Does everyone who has cysts on their ovaries have PCOS?

One common misconception associated with PCOS is that *anyone* who has cysts on their ovaries has PCOS. Which isn’t true, because, in fact, everyone has cysts on their ovaries and they aren’t always cause for concern. “This is why I don’t like the terminology of PCOS.” Kirkham says. As she explains it, anyone who has ovaries stores their eggs in cysts (“a little fluid filled ballon”). “So we have cysts every month and then they pop or ovulate and then two weeks later we have a period if we’re not pregnant.” Sometimes, these cysts can rupture—which can be very painful and may take someone to the emergency room, she says—but this popping happens every month and is not indicative of PCOS.

When it comes to PCOS, Kirkham says the main gynaecological basis for the period problems is due to an-ovulation, meaning people stop ovulating and cysts don’t pop. “And so that’s why you end up with a lot of cysts on the ovary,” she says (a.k.a polycystic). As opposed to your typical ovaries, “when they do an ultrasound, it almost looks like a pearl necklace, where all of the little cysts are around the edge of the ovary.”

One thing to be aware of is the fact that a lot of teens can have polycystic-looking ovaries and not suffer from PCOS. “They’re very hormonally active at that time,” Kirkham says, “so their ovaries are really ramped up and there’s a lot of eggs there.” Which is why it’s important to refer to the Rotterdam criteria, and not base assumptions or diagnoses of PCOS off of one symptom alone.

Is PCOS hereditary?

While doctors haven’t identified any specific genes that would indicate PCOS is hereditary (ie: passed along through familial lines), “there are PCOS-specific susceptibility genes that are being investigated,” Kirkham says.

How does PCOS affect reproduction?

If you’ve heard anyone talk about PCOS, chances are you’ve probably heard them talk about infertility. PCOS is often connected to infertility, because people with PCOS may have difficulty releasing eggs (thanks to an excess of androgen hormones). “About 25 to 30% of PCOS patients have fertility issues,” Kirkham says. (In fact, she continues, some places say even up to 80% of individuals with PCOS can struggle with fertility). But, the good news is that—as opposed to other syndromes like untreated endometriosis—the rate for infertility is much lower and can be more easily corrected. Also, we definitely shouldn’t refer to it as “infertility.”

“I wish we would stop using the term infertility because it is usually subfertility,” Kirkham says, “meaning a lot of people with PCOS still get pregnant.” In fact, Kirkham says, the type of subfertility with PCOS is probably the easiest one to treat, because it’s caused by an-ovulation. “So usually all you need is a medication to trigger the release of the egg,” she says. “So people may not need IVF and all of the whole gamut and the expenses of fertility treatment.” In fact, celebs who have PCOS—like model Romee Strijd—have spoken openly about their experiences with subfertility due to the syndrome. In a May 28 Instagram post, Strijd announced that two years after revealing her PCOS diagnosis, she was pregnant after making lifestyle changes. “To the women trying to conceive, believe in yourself and be nice for yourself and your body and don’t let those thoughts get to you too much,” Strijd encouraged her followers in her post. (And FYI, according to Kirkham, 70% of women with endometriosis do get pregnant).

How is PCOS treated?

While treatment for PCOS should be individualized—for example, Kirkham says, “for a teenager or a young person, they may be most affected by self esteem issues that they have with acne or unwanted hair; so in that case, that would be where we want to balance the higher androgens that cause those symptoms. So something as simple as a birth control pill that has female hormones in it will help balance out the antigen side effects”—Kirkham also says that “lifestyle changes; eating well, exercising and weight loss is treatment number-one for PCOS.” In fact, according to her, 10% weight loss has been shown to lead to spontaneous ovulation, which is why she advises that anyone looking to make lifestyle changes work in conjunction with a nutritionist.

“Nutrition and lifestyle modifications are the primary treatment approaches for [people] with PCOS,” says Trista Chan, a registered dietician and founder of The Good Life Dietician, who works with clients who have PCOS. While Chan says that there’s no ”optimal or gold-standard diet for PCOS treatment,” and treatment varies greatly depending on the individual, she places a strong emphasis on minimally processed, whole foods. “This means whole grains, legumes, nuts, leafy greens, berries and fruit, seeds, fish and chicken,” she says. As people with PCOS typically have higher insulin and inflammatory markers, Chan advises incorporating more anti-inflammatory foods like fish, legumes, green leafy vegetables, nuts, seeds and low-fat dairy, which she says have been shown to reduce inflammation and potentially regulate menstruation. “All of these interventions also usually lead to weight loss and improvement in metabolic and reproductive health,” Chan says. Another important note from Chan? “Exercise!”

It’s important to emphasize that advocating for a healthy lifestyle and exercise doesn’t mean that you need to become thinner or look a certain way. PCOS can affect anyone at any body size. It’s about figuring out what works best and is healthiest for your body.

And while there’s no foolproof way to ensure you won’t be diagnosed with PCOS, “the only thing that you can do to decrease the chance of being diagnosed with it is living a healthy lifestyle,” Kirkham says. “Making sure that you keep your weight stable (with the help and advice of a doctor) and then also knowing your family history, because if it’s in your family and there is some predisposition to it, you would want to track your periods and make sure they’re happening regularly.”

“It’s not something you can prevent, per se,” Kirkham continues. “You may be predisposed to it just like some people are predisposed to other diseases.”

Does PCOS every fully go away?

While PCOS can never be 100% completely cured, “nutrition and lifestyle modifications can be very effective in balancing hormones and relieving symptoms,” Chan says. And, it’s important to get diagnosed early so that you can increase fertility for those looking to conceive and prevent more long-term effects like diabetes, high blood pressure, cholesterol problems, sleep apnea, depression and anxiety, and uterine cancer.

And for anyone looking to keep their ovaries healthy and in tip-top shape, whether or not you have PCOS, Chan has some recommendations: “Filling your plate with inflammation-fighting foods is always a good idea,” she advises. “Berries are an antioxidant-rich, low-sugar fruit.” (She recommends eating them three times a week.) In addition, “low-fat yogurt, three to five times a week is also great source of calcium and probiotics to keep a healthy gut; fatty fish—like salmon or mackerel—are rich in omega-3 fatty acids, which play large role in reducing inflammation, boosting heart health, and there is increasing research linking it to hormone balance.”

Regardless of which route you take in treating PCOS—or general reproductive health—the most important thing is to consult a doctor and do what’s best for you and your body.