The Grandiloquence of André Leon Talley

At the height of The Philadelphia Story (1940), a classic American romantic comedy, there’s a brief moment of profound sadness. “You’re going to sell The True Love… for money?” asks Katharine Hepburn. On the receiving end of the question is Cary Grant, who, in the film, plays Hepburn’s old flame; The True Love is the boat which consummated their dilapidated love. Despite the gravity of this scene, where Hepburn is a weeping madonna, there is such elusive beauty in her speech, which is neither British nor American, but rather, both—a Hollywood accent that was once the classist hallmark of aristocratic (white) America.

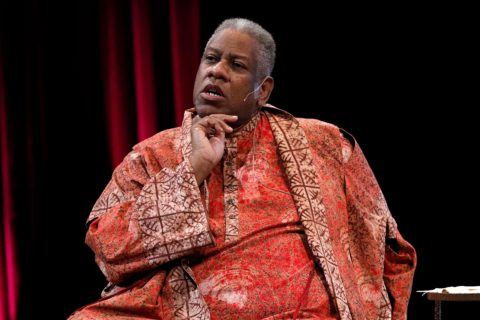

I thought of this manner of speaking as I watched The Gospel According to André, a documentary exploring the life and career of former Vogue editor André Leon Talley, which premièred at Toronto’s “Inside Out” LGBT Film Festival last week. The film is replete with what Anna Wintour calls “Andréisms,” a florid language author Hilton Als describes as “an old-school Negro syntax, French words (for sardonic emphasis), and a posh British accent.”

“This is André Leon Tally, reporting live from Paris,” Talley might say, softening his vowels and emphasizing his t’s. Or, “This collection is more divine than the last, Monsieur Ferrè, in that it is a high moment of Grecian simplicity, of fluted skirts in the material of a high rustling mega-moment, from room to room, à la the essence of King Louis XV, à la the true spirit of couture!” When Talley’s childhood friends speak, their voices are consumed by a Southern twang; André’s voice seems to reach for the archives, overriding his childhood syntax, affecting his best impression of a white woman.“You can be aristocratic without having been born into an aristocratic family,” says Talley.

André Leon Talley was born in 1949, in the Jim Crow South, where the only white person who ever entered the home he shared with his grandmother was a coroner. He didn’t know he was poor. He just knew he was Black. Others seemed to notice it, too: at Duke University, where Talley would visit as a teenager to buy copies of Vogue, white boys hurled rocks at him.

The Black enclave of Durham, N.C. where Talley grew up carries a rich history in civil rights protest. In the boutiques his grandmother visited, Black women were forced to wear veils to try on hats. Booths in ice cream parlours were segregated. Blacks and whites didn’t go to school together. In 1957, it became the site for the first sit-in of the Civil Rights Movement, where Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his famous rallying cry: “Fill up the jails!” Racism was the sinister backdrop against which Talley constructed his identity—the film is less about fashion than it is about the spectre of discrimination, and how no level of success can eradicate the demons of racism.

Churches were segregated, too. Talley sees his childhood as being very similar to Truman Capote’s A Christmas Memory. Raised by his grandmother, he was completely insulated from the outside world—except for church, which was the axis on which his entire life turned.

In church, André found style. It is here, I imagine, that the young fashion maven began crafting his dialect. Certainly he would have been exposed to Black sermonic tradition, a slave-origin dialect characterized by hyperboles, musicality, and an exaggerated, grandiloquent cadence.

Some of the greatest orators of our time seem to find wisdom in the caffeine thrill of the Black preacher’s eloquence—Barack Obama, Oprah Winfrey, Nelson Mandela. In a piece for the New Yorker, writer Doreen St. Félix beautifully captures the seemingly paradoxical thrill of Whitney Houston’s vocal artistry: “Idolatrous children thought she spoke like a princess. But American princesses, historically, have not had an Afro and been deeply brown-skinned; they have not been born in Newark, three years before a race riot.” The sentence could have been about André.

“Your voice expresses you,” Edith Skinner, the Canadian author who wrote the text that officially coached actors in the Transatlantic accent, once said. “You don’t want to lose that individual voice God gave you. What I try to do is get rid of the most obvious regionalisms, the accent that says, ‘you’re from here and I’m from there,’ the kind of speech that tells you what street you grew up on.”

Talley’s oratorical language—his unabashed black vernacular (“darling,” “chile”); his swanky British italics; his careful French exclamations (he studied French at Brown); his firsthand empirical knowledge—might have been among his greatest tools in navigating fashion’s largely white and often racist environs. His voice is essential as his talent; or perhaps, it is a talent in its own right.

Talley was as inspired by Martin Luther King, Jr. as he was by Lady Ottoline Morrell. That he appropriated a socialite’s lexicon, then weaponized it with his massive black body and subsequently metamorphosed into the image of glamour and aristocracy and fashion, is both confounding and alluring. The way he instinctively interrupts his white interviewers, his voice simply washing over theirs, like elocutionist kisses, seems to say: “I am just as important as you, and you’re going to hear my voice now.”