Designer Kerby Jean-Raymond Calls out Business of Fashion’s Inclusivity Problem

"Diversity and Inclusion is a trend for these folks," he wrote on Instagram. "BoF 499, I'm off the list."

Purportedly celebrating the most influential people in the global fashion community—from stylists to editors to models to designers—Business of Fashion’s annual BoF500 list has become an industry-wide badge of honour in the seven years that the publication has been putting it out. This year, celebrated New York designer Kerby Jean-Raymond, who helms the brand Pyer Moss, was part of that coveted list of 500 individuals. However, the day after the gala was held in Paris on September 30, he published a lengthy statement on Medium calling out the cultural appropriation and insensitivity he witnessed at the gala event, and why he wished to no longer be associated with the BoF500 list.

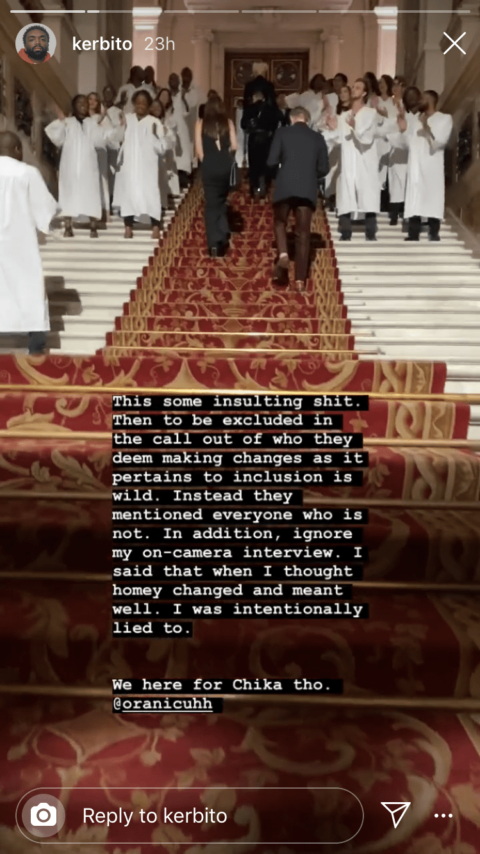

As a designer whose work has long addressed “the erasure of African American narratives in popular culture,” Jean-Raymond’s NYFW shows each season celebrate black culture, music and history with a care and thoughtfulness often missing in the fashion industry. Choirs have been a mainstay of his shows since 2015, when he first assembled the Pyer Moss Tabernacle Drip Choir, so walking into the BoF Gala only to be greeted by a black gospel choir performing “to a room full of white people” understandably set him on edge.

“That level of entitlement is the core issue,” he writes. “People feeling like they can buy or own whatever they want … if that thing pertains to blackness. We are always up for sale… Homage without empathy and representation is appropriation. Instead, explore your own culture, religion and origins. By replicating ours and excluding us — you prove to us that you see us as a trend. Like, we gonna die black, are you?”

Aside from the insensitive decision to have a black gospel choir perform at a fashion event in Paris, Jean-Raymond also outlined other ways in which the publication and its editor, Calgary-born Imran Amed, “gaslighted, used, monetized and then excluded” him from the BoF500 issue. In the months leading up the issue, Jean-Raymond says he was approached by BoF to participate in their Voices panel series, for which he would be interviewed by model/activist Bethann Hardison. Refusing most other panels because of their tendency to lump him with other black designers to speak on the topics of diversity and inclusion, and homogenizing their experience in the process, Jean-Raymond agreed to participate in this solo interview only to learn much later that it been turned into a group panel with two other black designers.

“I did it, begrudgingly,” he writes. “But in reality all three of us have our own unique narratives and histories that warranted our own separate solo stages. The same solo stages that all the other white designers have received, for years.”

He adds that he later participated in a “heated and problematic” Salon conversation that was so insulting he left the BoF event two days earlier than planned. Despite these “degrading” events, he agreed to speak with Amed when he reached out a few months later with the news that he would be featured on one of the magazine’s three BoF500 covers for his contributions to the fashion industry. “In all these calls and talks he’s picking my brain for names to include on this cover with me and a list of “diverse” people for the 500,” writes Jean-Raymond, who felt at the time that “something was off.” Sure enough, he was informed later that the publication had decided to go “a different route.” (Eventually, the three covers turned out to feature Harlem-based designer and Gucci collaborator Dapper Dan, Alabama rapper Chika Oranika, and Valentino designer Pierpaolo Piccioli alongside South Sudanese-Australian model Adut Akech.)

Somehow, Jean-Raymond says, he was able to put all that aside and was convinced by friends to attend the BoF Gala—where things went from bad to worse.

“I’m offended that you all made those beautiful black and brown people feel really terrible to the point where some of my friends said “this is helpless”, “this shit will never change” and others left in tears,” he writes. “I was fine until they weren’t fine.”

Some of the other people of colour at the BoF Gala offended by the event include Aurora James, the Toronto-born founder of shoe brand Brother Vellies and Elaine Welteroth, former editor of Teen Vogue. In one of a series of Instagram Stories posted from the event, Welteroth writes, “Inclusivity or Appropriation? The answers are clear when a black gospel choir is used out of context as a backdrop for a mostly white audience in Paris, all in the name of inclusion in fashion. FYI Black culture is not a trend. I am not one to promote call out culture but as someone who grew up in a black baptist church my ancestors won’t allow me to absorb this shock silently. The paradox here is stunning.”

Aurora James, in another series of several posts, writes about BoF’s disingenuous attempt at inclusivity by hiring a black gospel choir to sing “songs that were intended for sacred black religious safe spaces,” adding that “this is just the further commodification of black culture for corporate gain. That type of cultural appropriation under the guise of inclusivity is exactly the opposite of what we need to be doing.”

She further commented on Imran Amed’s response to Jean-Raymond’s statement, in which he largely focuses on his own affection for choir music and his experience as the son of immigrants in Canada, saying that he has many others to apologize to, including all of the other black and brown people in the room.

“Kerby has every right to voice his concerns and we respect his perspective,” wrote Amed in his response. “He is also right about several things. As Kerby points out, the fashion industry has often treated inclusivity as a trend, putting diverse faces in our ad campaigns, on our runways, on our magazine covers and, yes, at our parties because it’s cool and of the moment. But I can assure you that this topic is not a trend for BoF.”

He goes on to write about how, growing up, he always felt like an outsider. “This is one of the reasons why I set out to build an inclusive culture at BoF, where our 110 employees come from almost 30 different countries and many different races, genders, socio-economic backgrounds and sexual orientations.”

This sounds great in theory, but as fashion podcaster Shelby Ivey Christie pointed out on Twitter last week, the BoF team doesn’t look quite as diverse as one might hope.

Here’s the photo of their team that Business of Fashion currently has on their career page ?? pic.twitter.com/sVQVpagkLu

— Shelby Ivey Christie (@bronze_bombSHEL) September 23, 2019