Treating My Depression with Magnets: Not Cured, But Cautiously Optimistic

I took part in an intensive study involving repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation—in other words, pressing magnets to my skull. Here, I share *exactly* what it was like—and the results I experienced

One morning last November I got into a cab and told the driver I was going to Toronto’s Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. I said it very casually, hoping that he wasn’t the chatty type. He was.

“So you are a psychiatrist?” he asked as we coasted down the street.

“Nope,” I said, staring intently at my phone.

“Oh. A counsellor, then.”

“No. Just a regular patient.”

“Ah,” he replied, then after a moment of contemplation: “So do you have an addiction or a mental health?”

I told him that I didn’t have either, but was hoping to get a mental health.

Why I decided to try repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation

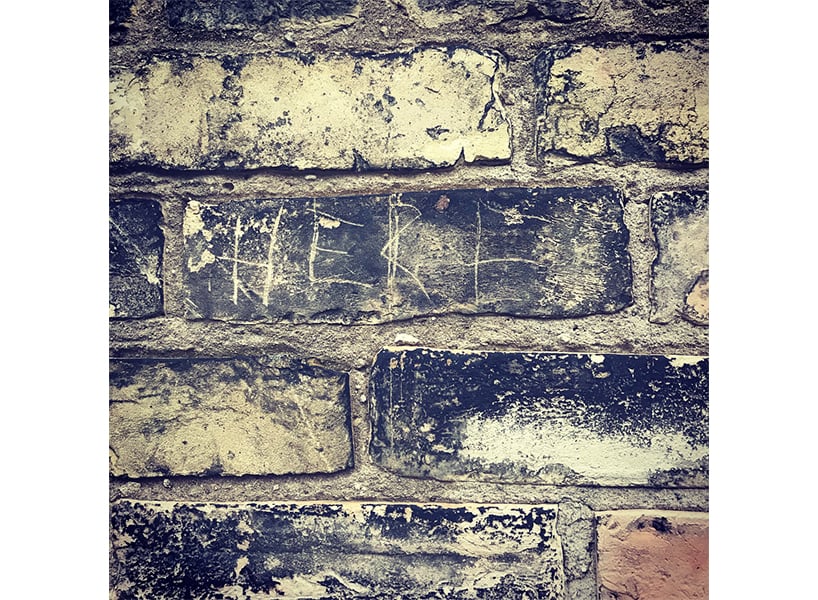

There has been a psychiatric facility on what is now Toronto’s Queen St. W. since the mid-1800s, when it first opened as the Provincial Lunatic Asylum. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health (commonly referred to as CAMH), occupies the same lot as the Asylum, although nothing of the latter remains except for two old storage sheds and the huge stone wall that encircles the grounds. The wall was built by patients shortly after the Asylum opened; manual labour was thought to have great benefits in treating the mentally ill. Whether or not this is true, the benefits of having a large labour force that they never had to pay were certainly not lost on the Asylum’s administrators.

The site has gone through many physical changes since the Provincial Lunatic Asylum first opened, as well as a few name changes and one symbolic change of address (from 999 Queen Street West to 1001 Queen Street West–“999 Queen,” a nickname for the old Asylum, carried a strong stigma with it). These days, CAMH is in the process of being revitalized once again. The buildings closest to Queen St. are brand-spanking-new, all huge windows and gleaming steel, as clean and light-filled on the inside as they seem on the outside. Behind them, crouched like gargoyles, are the older buildings—brutalist concrete hulks from the 1970s. It was into one of these buildings, Unit 4, that I was heading that day in November. Far from being put off by Unit 4’s appearance, I felt strangely satisfied. It looked exactly like I felt.

I’ve had clinical depression since my early teens, which means that more than half my life has been coloured by its presence. It waxes and wanes, like most chronic illnesses, but usually I’m able to stay reasonably functional thanks to antidepressants and therapy. In 2017, however, my depression bloomed to its ugliest and fullest. I’d been teetering on the edge of a bad episode for months, and then in March I’d had an adverse reaction to a new medication that left me unable to sleep even with the strongest prescription sleeping pills. That had led to a breakdown, then a suicide attempt, and finally a two-week stay on a psychiatric ward. By November I was better, but better is a relative term; when it comes to mental health, better than suicidal is a fairly low bar and I’d been stuck for months in the stasis of not wanting to die but not particularly wanting to live. Nothing seemed to help, not even the fancy new antidepressant the hospital had put me on.

I was at CAMH to participate in an intensive study on a relatively new therapy for drug-resistant depression: repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (or rTMS). My psychiatrist knew about the study and gave me a referral, although she warned me that it would likely be months before I heard back. But as luck would have it they had one slot left for their next rotation, so I was able to start the week after my initial assessment.

What is rTMS?

“Transcranial magnetic stimulation involves powerful electromagnetic field pulses that act on circuits in the areas of the brain that control mood,” says Dr. Daniel Blumberger, the director of the rTMS for depression study at CAMH. “It alters the way the circuits of the brain are connected.” In other words, strong magnetic currents were going to be applied to my head, in the hopes of remedying the faulty wiring that was causing my depression.

Because the layout of everyone’s brain is slightly different, before I could get started the rTMS, the specific shape of mine needed to be mapped. First I had an MRI, which produces detailed pictures of organs like the brain; then my head was greased and wired up for an EEG, which records the brain’s electrical activity. After these tests, technicians worked to pinpoint the exact part of my motor cortex that controlled my right thumb. Using all this information, they would have a decent idea of what was where inside of my head. Finding the correct part of my motor cortex involved sitting in what looked like a dentist’s chair while three techs fluttered around me, adjusting and readjusting the various wires and instruments to which I was attached. They pressed a heavy magnetic coil to my head, moving it from one spot to another to try to find this one elusive wrinkle in my brain. I kept my arms deliberately limp and relaxed, but for a long time nothing happened. Then suddenly, my thumb started twitching; it felt like magic.

No, not magic. Science.

Still, I couldn’t get around how, well, magical rTMS sounded. I should probably clarify at this point that I am not a very scientific person; I am the kind of person who nodded their head in agreement as the Insane Clown Posse wondered aloud “Magnets, how do they work?” When my psychiatrist tried to explain to me that pressing magnets to my skull could alleviate my depressive symptoms, it sounded not unlike when people say that vibrations from certain crystals can heal you. Probably harmless, sure, but not exactly helpful. Yet at that point—after exhausting almost every other avenue of treatment—I was willing to try just about anything.

The science is solid, but there’s a small catch

In spite of my reservations, the science behind rTMS is quite solid. It’s not exactly new, either; its efficacy in treating various neurological and psychiatric conditions has been researched since 1985.

“Using rTMS to treat depression has been very vigorously studied over the last 20 or so years,” says Blumberger. “It’s been shown across multiple larger-scale randomized trials to be better than a placebo.”

One of these larger-scale, randomized trials, done by the National Institute of Mental Health, showed that participants who receive rTMS are four times as likely to have some kind of remission compared to participants who received a placebo. Overall, participants in this study had a remission rate of about 30 percent. Other studies have shown an even higher remission rate.

As well as having modestly decent effectiveness in treating drug-resistant depression, rTMS also has fairly mild side effects (in a very, very small portion of patients—less than 1 percent—it can cause seizures; more common side effects are headache and dizziness). And unlike electroconvulsive therapy, which has a higher remission rate than rTMS but carries with it a host of complex side effects, rTMS does not require sedation and there is no post-treatment recovery time needed.

So what’s the catch? Well, the “repetitive” part, as it turned out. To partake in the study I had to agree to 30 consecutive treatments; including travel time to and from the hospital, it mean sacrificing a two-and-a-half-hour chunk out of the middle of my work day. Five days a week. For six weeks.

My first treatment session

On the first day of my treatment I was led to a small room at the south end of Unit 4. Nadia, the tech I would be working with for the next six weeks, gave me a pair of earplugs and marked two dots on the front and back of my head with a green pen. The magnetic coil was placed on the dot at the back of my head and the Nadia switched on the machine. It made a lot of noise, but I didn’t feel anything. Out the window, I saw one of Toronto’s legendary white squirrels playing on the wall the patients had built. I took it as an auspicious omen.

For the study I participated in, rTMS treatments are administered in two sessions—one at the back of the head and one at the front. Each session takes about five minutes, with a 50-minute break in between, and is comprised of 600 magnetic pulses.

As I settled in for the second part of my first treatment, Nadia explained that for some people the rTMS feels different at the front of the head. The bones of the skull are thinner there, she said, and so I might experience more sensation during this session.

The rTMS at the front of my head felt like a tiny, sharp mallet hitting my skull over and over. As it was happening, I suddenly remembered a friend who had also undergone the treatment, saying that it felt like getting a tattoo on her brain. That, it turned out, was an entirely accurate description. The rTMS also made my facial muscles twitch uncontrollably, so that I looked like I was snarling with every pulse. I felt my eyes well up with tears, and I blinked hard, trying desperately not to cry.

Later, when my first session was over, I walked over to the stone wall outside and genuinely did cry. There are names scratched all over the bricks, people who had been here before me, people who had struggled in some of the same ways that I had struggled. Many of the names were followed by the letters R.I.P. It was one of those wet, bitterly grey days and everything felt supremely unfair. Being depressed wasn’t fair. Being too sick to work wasn’t fair. Being trapped forever in this malfunctioning brain wasn’t fair. None of the people whose names were on the wall had been dealt a fair hand. I leaned my head against the cold bricks and wept until my chest hurt and I couldn’t catch my breath.

Sticking with it

I stuck with the rTMS, though. After five days of it, I bought myself a chocolate cupcake with a full two inches of hazelnut frosting to celebrate the end of my first week. Midway through the treatment I bought myself an enamel pin shaped like a white squirrel, and put it on the breast of my winter coat.

I taught myself tricks to move away from the pain of the second session—instead of thinking about my body, I would picture the house I grew up in, room by room, detail by tiny detail. What was the exact angle of the skylight in my old bathroom? What colour was the linoleum in the kitchen? Somehow working through these questions made the tiny mallet’s pounding bearable. As the weeks went on, two things happened: I developed a meticulous mental map of my childhood home, and my mood started to stabilized.

For the first time in over a year I was OK. Not great, not terrible, but OK.

OK had never felt so incredibly good.

After 30 treatments

I just finished my final rTMS treatment last week, and I feel cautiously optimistic. It’s possible that this upswing in my mood is a random blip, but on the other hand this is the first January in over a decade that hasn’t found me hunched on my bedroom floor at 2 a.m. scream-crying into a pillow because my life feels intolerable. I doubt that I’m cured—I’ve been too depressed for too long to believe in cures—but I’m managing. If that sounds like an incredibly low standard of living, please remember that two months ago the best I was able to feel was not actively wanting to die. I’m hopeful that I’ve entered that state of remission all those rTMS studies talked about. If I have, then it’s possible that I’ll need maintenance treatments every few months, but that seems like a small price to pay for a healthier brain.

I was very fortunate to be able to participate in the rTMS study at CAMH. For one thing, my schedule as a freelance writer was flexible enough to allow me to do it (something I cannot imagine many workplaces tolerating). For another, I live in one of three provinces in Canada (the others are Quebec and Saskatchewan) where the treatment is covered, but only for research purposes. That has to change. As someone who lives with mental illness, it often seems like our much-vaunted Canadian healthcare systems fails the mentally ill and fails them hard. Medication is expensive, and psychotherapy isn’t covered. Many government-funded cognitive behavioural therapy programs run during business hours, making it difficult for people working on a 9-5 schedule to access them. Keeping my head above water often feels like a full-time job.

When I asked Dr. Blumberger if he had anything he wanted to add to the what he’d already told me, he said: “The hope is that we continue to push the people responsible for funding healthcare to further invest in mental healthcare and novel treatments that have demonstrated efficacy.”

I have never felt more like standing up and raising my hands and yelling AMEN.

More from Anne Thériault:

The Way I Was Treated at a Hospital After My Suicide Attempt Was Humiliating

People Who Die by Suicide Don’t Forfeit the Right to Privacy

Remember the Women of the Montreal Massacre by More Than Just Their Names