Do We Really Need Another Season of You?

**Spoiler alert** This article contains details about 'You' seasons 1 and 2

In the past year, when friends or coworkers have asked for my feelings on the Netflix series You, I have either dodged the question or acted with a sort of ambivalence. “It’s compelling,” is the most I’d offered up.

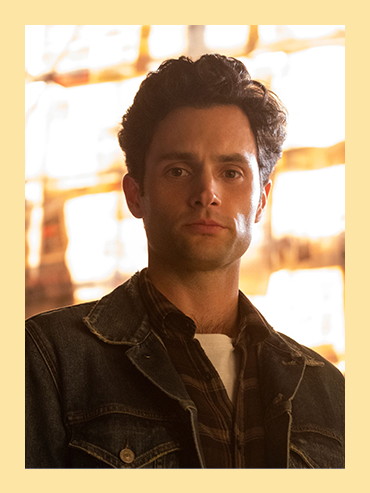

The truth, of course, is that I rather enjoy the series—the epitome of a guilty pleasure. An expertly-made confection, You is buoyed by a few strong performances, slick production values and captivating twists. The first season is a lot smarter than it needs to be, constructing a traditional romantic hero in Joe (Penn Badgley), encouraging us to empathize with him, and then upending our expectations by revealing him to be both a stalker and murderer. It’s a clever bit of genre rug-pulling, giving the show the opportunity to indulge in both romantic comedy and true crime tropes while also seeming hip to recent discussions about how romantic comedies can normalize stalking behaviour.

But at the end of the first season, when Joe kidnaps and ultimately murders his girlfriend Beck (Elizabeth Lail), I didn’t feel OK about enjoying it anymore. For all its glib, tongue-in-cheek awareness, it’s ultimately problematic in the way that many thrillers and romantic comedies portray stalking—a charming murderer, always one step ahead of his (mostly female) victims, a trail of destruction glossed over, and a privileging of the male killer’s point-of-view.

And this glamourizing of stalker behaviour can have real-life consequencces. “Media portrayals can wear down a woman’s ability to recognize the red flags,” says women’s rights advocate and public educator Julie Lalonde. “It can delay our ability to respond [to stalking] because we’ve been encouraged to view that behaviour as romantic for so long that it becomes hard to recognize when a person is a threat.”

I left the first season finale questioning if I’d be able to stomach additional seasons of the show, which were inevitable given its enormous popularity. (This month, it was announced that a third season is on its way.) Was this what I had truly signed up for? A series in which an arrogant stalker would always prevail, and an innocent woman would always be his victim? A show glamourizing stalking that, according to StatsCan, has occurred to 1 in 20 Canadians?

The second season, released last month, seems aware of these larger concerns (not to mention public criticism) and tries to deal with them in a way that keeps the fundamental DNA of the show intact. Once again, Joe is obsessed with a beautiful young woman, the aptly-named Love (Victoria Pendretti), and once again we see the way he insidiously integrates himself into her life, gaining the trust of her friends and family. But whereas the first season revels in Joe one-upping Beck and the vapid New York literati, the new season takes a different, decidedly film noir approach. The version of Los Angeles that Joe inhabits is one where he is merely a narcissistic sociopath in a sea full of narcissistic personality types, all with their own obsessive pursuits. The new characters, many of whom are female, are all one step ahead of Joe, and navigating their own shifting moral codes. This is a world of investigative reporters, mobsters, pedophiles and police cover-ups. It’s straight out of a Raymond Chandler novel—if all the characters weren’t also reading Raymond Chandler.

And as much as Joe tries to position himself as morally superior to those around him, he is continually confronted by his own monstrosity. In one of the season’s most affecting scenes, Joe ties up a Hollywood celebrity (played by Chris D’Elia) who has been drugging and secretly filming underage girls, threatening him with death if he doesn’t confess on camera. But the actor sees right through it, drawing parallels between his depravity and Joe’s actions. “You hate yourself, so you’re trying to destroy me. We’re the same… You’re a piece of shit, so you’re trying to be a hero. Ruining my life isn’t going to save you from your demons,” he says.

This confrontation is mirrored in the season’s most interesting twist, when Joe learns that his girlfriend is not the clueless victim he made her out to be, but a charming sociopath like himself. As Love locks him in his own cage and reveals the homicidal lengths she went to in order to be with him, Joe balks, viewing the revelation as a betrayal of his own moral code and his initial conception of her. He recognizes the parallel to his imprisonment of Beck in season one, but fails to see how he and his captor are similar. But Love takes the opportunity to set him straight: “While I was seeing you—really seeing you—you were busy gazing at a goddamn fantasy. A perfectly imperfect girl. You saw what you wanted to see.”

It’s a nice bit of comeuppance for Joe—forced to experience what his own victims have gone through, called out for how his obsessive fantasies have never been the noble romantic gestures he entertains them to be, and that the women he idolizes are more complex than he allows them to be. And while Joe ends the season obsessed with a new woman, he’s also trapped inside a prison of his own making—suburban marriage—with his wife and her family well-aware of his previous sins. He can’t merely escape.

And yet for these many course-corrections on the part of the show’s creative team, does this leave us in a better place in terms of representation? Does shifting the moral landscape around Joe change the show’s privileging of him as an empathetic hero? Looking at message boards for the series and Badgley’s own attempts to quell its fan base, it’s clear that many viewers still don’t recognize Joe’s actions as problematic, and perhaps they can’t be entirely blamed for that.

“In the context of [You], yes, theoretically we’re supposed to view this guy as creepy, but are we actually?” says Lalonde. “Have we raised people to have the media literacy to be able to see that this is not just entertainment, and that it’s really bad if you identify with him or shit on his victims?”

For instance, Love’s homicidal nature is a clever trick on the part of the show’s writers, sparing viewers from more gendered bloodshed on the series by putting the knife squarely in her hands, but it also gives Joe exactly what he wants, eliminating the women who would otherwise get in his way—one of whom is a former victim (Ambyr Childers), traumatized by her abuse at his hands.

In contrast, Joe ends up saving two people in the second season, a man he kidnaps and ultimately frees, and a teen he keeps from entering the foster system after she is orphaned. The only murders he is directly responsible for are “not his fault”—criminals he kills in either self-defence or by accident.

And the series continues to delve into his psychology through flashbacks and his point of view, showing the roots of his actions as possible by-products of neglect experienced in childhood, an attempt to unpack something that perhaps doesn’t need to be unpacked.

“A lot of the discussion of the show has centered on it being from [the stalker’s] perspective, and that this provides some sort of insight into what these kinds of people are thinking or the cause of their behaviour,” says Lalonde. “Look, we already know. It’s misogyny. We don’t need to find some deeper meaning to it, or to learn that he hates his mom.”

By keeping Joe front, centre and (even inadvertently) victorious, the show continues to be problematic, regardless of its portrayal of female characters.

“The key to accurately representing stalking is striking a balance between seeing what the violence is, but also psychologically what it does to the victim,” continues Lalonde. “Stalking is psychological terrorism, it is this person living inside your head and you not being able to shake it. Those psychological elements are missed when we focus on the psychology of the stalker instead of the impact and the psychology of people who have been victimized.”

“And that’s not raising awareness. It’s damaging.”