The Best (and Angriest) Books of the Moment

"Any book that provides an alternative narrative to the one we’ve read throughout history, that of women as angelic, quiet, and acquiescent, should be celebrated."

We’re living through a critical moment in history where women’s anger is simultaneously being challenged and used as a revolutionary force. The expression of women’s ire through the #MeToo movement and women’s marches is heartening. But a quick look at the gendered bias we see towards anger in the public sphere tells us they’ve by no means stopped the inertia of patriarchal status quo.

Non-fiction authors like Rebecca Traister and Soraya Chemali have tackled the delegitimization of women’s anger in their books Good and Mad and Rage Becomes Her, respectively, tracing the issue back in time through the suffragist movement up until the present day. Traister begins her book with a galvanizing call to arms: “We must come to recognize our own rage as valid, as rational, and not as what we’re told it is: ugly, hysterical, marginal, laughable.”

When it comes to sexual harassment, assault, or infringement on our reproductive rights, the only rational response is anger. But as Traister outlines in her book, we’ve been schooled to believe that anger is unladylike and unattractive and this has been reinforced through our punishment in the professional and political spheres when we do express it. In a study published by the American Psychological Association, when women and men were depicted with the same expressions of fury, people tended to view the women as more livid than the men, perhaps because of the socially-contrived incongruency between women and anger. If a woman looks angry, she must be really angry, the thinking goes, because isn’t smiling the default expression for women? Similarly, in a 2018 study by Arizona State University, both men and women viewing staged, impassioned closing arguments by lawyers found the angry male attorneys to be commanding, powerful, and competent, opposed to the female attorneys who were perceived as shrill, hysterical, and ineffective.

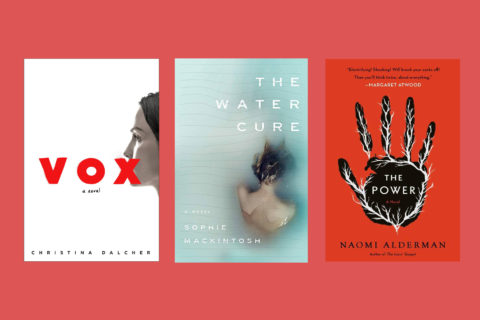

It’s not just non-fiction that’s taking up these issues. A new wave of feminist fiction is challenging and subverting the way women relate to their anger and the inextricably linked systems of power that shape our society. Later in the summer, English author Rosie Price will drop her debut novel, What Red Was about sexual violence among the upper class. In The Water Cure, three sisters live in a dystopic world where men are quite literally toxic and their parents, Mother and King, keep the women “protected” through water therapies (reminiscent of those used on ‘hysterical’ women throughout history), and other forms of self-harm meant to abate their emotions. When three men wash up on the shores of the sisters’ home, their carefully-contained world quickly crumbles under the force of the women’s desire and rage, which shifts the power paradigm in dark and unexpected ways. “I felt angry writing the novel, I felt powerless,” says Mackintosh. “I was conscious of the fact that women are so often disregarded, belittled, or written off as overreacting when it comes to anger and pain.”

The use of water therapy — or as it’s referred to in the book ‘the drowning game’ — to supress the sister’s feelings, be it desire, anger, or sadness, mirrors the rhetoric we’ve been seeing in the public sphere that reinforces angry women as hysterical or unhinged. Think of the deeply engrained gender stereotypes we witnessed in action during the fiery, emotive testimony of Brett Kavanaugh compared to Christine Blasley-Ford’s polite, palatable anger during the Kavanaugh hearings. Amazon’s documentary Lorena takes up this issue by highlighting how Lorena Bobbitt’s justified act of violence against her abusive husband in 1993 — she famously cut off his penis after he raped her — was reduced to nothing more than a punchline by the media. Even her plea of temporary insanity during the trial works to undermine and negate what is in fact a rational response to rape.

The sisters’ violence in The Water Cure acts as a cathartic reclaiming of their strength and agency. It’s a theme echoed in Naomi Alderman’s work of speculative fiction. The Power imagines a world much like our own, only teenage girls and women are suddenly gifted with an unbridled physical power. With the point of an index finger, women are able to inflict severe pain on anyone who crosses them. In Alderman’s world, women wield the power in terrifying ways, offering a chilling analysis of how power structures are established and maintained. And isn’t this why women’s angry voices are so scary to so many? An angry majority would pose a real threat to the dominant systems of power in our world, systems that predominantly favour a white male minority.

It’s no coincidence that many of these works of feminist fiction take place in a dystopic setting. “Speculative fiction offers an opportunity for imagining the world otherwise and so it can be radically subversive,” says Hannah McGregor, professor of publishing at Simon Fraser University and host of the podcast Secret Feminist Agenda. “The fantastic offers space for a different way of seeing the world, sometimes framing the world within an explicitly feminist or non-patriarchal worldview.” It’s not the first time female authors have turned to fiction to express discontent with the status quo. McGregor points to the wave of suffragist fiction that appeared at the turn of the 20th century, such as Herland by Charlotte Perkins Gilman which takes places in an isolated society composed entirely of women.

Although heavy-handed in its message, Christine Dalcher’s novel Vox continues this tradition by begging the question, what would happen if the last vestiges of women’s rights were actually stripped away? Dalcher distills the current anxieties around women’s freedom down into a dystopic narrative reminiscent of The Handmaid’s Tale in which women are literally prevented from speaking, allotted an oppressive 100-word-per-day limit. Should they transgress, they’ll receive an electric shock, or worse.

The decision to work with the limitations placed on women’s voices in a literal sense finds a stark parallel in the silencing of senators — and now presidential candidates — Kamala Harris and Elizabeth Warren who have both been told quite literally to shut up by male colleagues. In her feminist manifesto Women & Power, Mary Beard traces this systemic silencing of women in the public sphere back to Roman antiquity to show how deeply entrenched these beliefs are. “Public speaking and oratory were not merely things that ancient women didn’t do, they were exclusive practices and skills that defined masculinity as a gender,” writes Beard.

The cathartic rage that is central to these dystopic works of fiction also plays out in more realistic recent fiction such as Laura Sims’ Looker and The Perfect Nanny by Leila Slimani, although in ultimately less empowering ways. In both novels, the author subverts the notion of all women as good, kind, and maternal by placing violent anti-heroines at the centre of the narratives. While it’s refreshing to see women cast in these roles, it also capitalizes on the Fatal Attraction trope of angry, violent, unnatural women. The insidious warnings to female readers is clear: This is what could happen if you end up single and alone, in the case of Looker or to working mothers in The Perfect Nanny: If you go back to work your children might meet a grisly end.

For their faults, any book that provides an alternative narrative to the one we’ve read throughout history, that of women as angelic, quiet, and acquiescent, should be celebrated. At this pivotal moment when regressive politics and gendered violence poses a mounting threat to women, we need these empowering stories more than ever. Anger can be divisive but it can also be a powerful unifier. Rage stokes the flames of injustice in a way that creates action, protest, and change. The delegitimization of women’s anger stems from the fearful recognition of the most dangerous tool we have at our disposal: white hot fury.