When My Mom Got Breast Cancer, I Began to Wonder If I Would Too

A parent’s illness has a way of making you consider your own genetic predispositions, and it’s not always easy to deal with

Late last year, my sister and I shaved my mom’s head.

As far as cancer goes, my mom was lucky. A small tumour in her right breast was caught and removed early, and the cancer hadn’t spread to her lymph nodes. It was the best case of a very bad scenario. But, to be on the safe side and with the recommendation of her doctor, she opted for a round of chemotherapy and radiation. So, eight months after she was diagnosed, my mom sat in her bathroom with a towel over her shoulders as I ran a buzzer over what was left of her hair. She had completed 10 weeks of chemo and her hair was nearly gone, so other than some wispy bits, it was a mostly symbolic act. Even so, it felt like taking control of an otherwise uncontrollable circumstance—like a fresh start. But it also felt like foreshadowing.

Cancer runs in my family, and breast cancer leads the pack. Both of my maternal grandparents had breast cancer. Since my mother had two first-degree relatives with breast cancer (including her father’s extremely rare case), it wasn’t exactly a surprise that my mom was eventually diagnosed with the disease as well. But it wasn’t until I was shaving my mom’s head, that I realized there’s a very good chance that one day my kid or friend or husband would one day do the same thing for me, under very similar circumstances.

Finding out my mom had breast cancer was a shock to my system. I had kept relatively calm as she told me her diagnosis on the phone, but after ending the call, I broke down, crying into my husband’s chest in the middle of our living room, full of fear for her future. I quickly went into caregiver mode, focussing my energy and thoughts on her needs. It wasn’t until I shaved my mom’s head that I felt that fear creeping back in—but this time it was for myself.

My mom’s diagnosis changed my perspective on my own health

Since my mother’s diagnosis put my own genetic risk into sharp focus, I did the same thing I always do when I get scared—I researched. I became fixated on stats and breast cancer research, because I assumed this illness was some sort of warped family legacy I couldn’t avoid.

“If you’re watching someone you love go through an illness, it’s normal to think that this could happen to me,” says Emma Rinaldo, a social worker at the Peter Gilgan Centre for Women’s Cancers at Women’s College Hospital, a collaboration with the Canadian Cancer Society. “You see that you’re not invincible and it’s scary.” According to Rinaldo, some level of distress is inevitable for anyone who has a diagnosis, as well as for their family members or inner circle. For many of us, a parent getting sick is our first adult or first profound experience of mortality and fear of death is at the heart of a lot of anxiety surrounding illness.

It makes sense that my thoughts didn’t immediately go to my personal well-being—I was, after all, in good health. It also took time for my mom to consider the implications her family history of breast cancer could have on her own health. When her parents got sick, she chalked it up to poor lifestyle habits or bad luck. It wasn’t until she spoke to her own doctor about mammogram frequency that she realized—especially with her father’s diagnosis—she was in a new group of cancer screening. A high-risk one.

Then, when she learned she had cancer, her fear became wrapped up in her treatment more than her diagnosis, because of her experience with her parents’s illnesses. “The thing that really scared me was that, instead of going through chemotherapy a third time when she was diagnosed with bone cancer, my mother chose instead to die,” my mom says. “She died at the same age that I am now, and that scared the crap out of me.” Although she knew treatment had come a long way in the 20-odd years since her own mother’s death, it was a hard image to shake.

My mother being diagnosed not only confirmed her high risk status, it made me feel high risk, too. My mom opted to test for the BRCA genes, the gene mutations that can dramatically increase a woman’s risk of breast and ovarian cancer. She came back negative, but I had no idea what that meant for me. Without understanding the likelihood that I would get breast cancer, my mind immediately went to worst-case scenarios and rushed to make peace with inevitability.

What to do with that fear

It seemed necessary to focus on my mom during her treatment and it was easy to think about the steps to take to care for her—in fact they were laid out pretty clearly by her doctors. But it was harder to understand what I needed to do for myself to mitigate my fear, and to move forward once I started to redirect some of my focus back to my own feelings. While I did find much of my research helpful, it was research without direction, and it was difficult to determine what applied to me. When my mom mentioned that the practitioner who talked her through her genetic test results had offered to talk to my sister and I about what those results meant for us, I jumped at the chance to understand the disease on a more personal level—and to consider the steps to take to be proactive.

Often the key to managing your own anxiety about illness comes down to what Rinaldo calls “protective factors,” and they are useful whether you’re sick yourself or you love someone who is sick. These include education and facts, therapy and open communication. “Having answers can help ease anxiety,” says Rinaldo. Shawna Ginsberg, senior manager of support and education at Rethink Breast Cancer, recommends seeking out tools like genetic counselling as a first step if you’re not sure what a parent’s diagnosis means for your own future health. Sometimes you learn things that don’t make you feel better (for me this was how most breast cancer isn’t genetic, so even if I test negative for BRCA, that doesn’t mean I won’t get it) and some is comforting (Rinaldo reminded me that most breast cancer is treatable and that the perception of cancer as a death sentence isn’t accurate). But all of it helps you make informed decisions about your own health journey and your real—not imagined—risk.

Therapy and counselling, whether in a group or one-on-one, are also helpful ways to voice your anxiety and acknowledge your distress, while also learning tools to find a way through. And finally, if you can, talk to your family member who is sick and your health care team. “Ask questions and arm yourself with knowledge as a family,” says Rinaldo. “And keep those lines of communication open.”

While I’ll probably never be commended for my open communication skills, I am learning to ask questions—both to health care professionals and my mom—to better understand what this disease looks like and how it affects my family. As per Rinaldo’s recommendation, I’m working on my “protective factors.”

Where we are now

In the aftermath of her diagnosis, my mom opted to do further genetic testing to determine as much as possible whether her cancer was inherited. For her, knowledge is power and her high-risk, early screening had already saved her once. (Her tumour was so small that it couldn’t be felt—it was only seen as a little star on her mammogram. Without the mammogram it would not have been caught so early.) Eighteen more genes were tested, and BRCA 1 and 2 were retested and they all came back negative. Despite our family’s history, it’s unclear—though unlikely—that my mom’s breast cancer resulted from an inherited gene.

That’s good-ish news. It means that based on these tests, there is no indication that my mother, my sister and I have an increased risk of breast cancer. But, because of our family history, I’m not exactly considered low risk, either. In fact, I qualify for high-risk screening beginning at 30 (which means a mammogram and MRI every year). My next step is to determine when and if I want to begin that screening. For me, it’s a no-brainer. I’ve already received a referral and at about the time I celebrate my 30th birthday later this month, I’ll meet with doctors to learn more about the high-risk screening process.

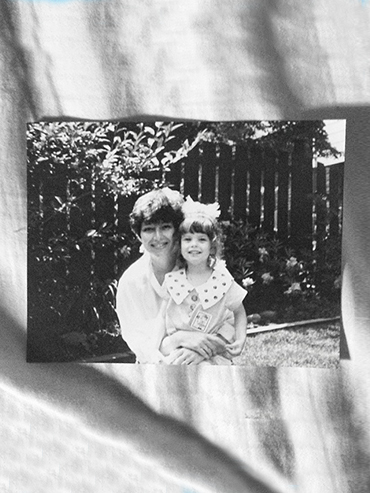

After my sister and I finished shaving my mom’s head, we took a photo. My glance is down, towards the screen of the phone I’m holding to take the photo, a little disconnected, a little pulled back. My sister—an amazing pillar of light throughout the whole process—looks into the camera with a full smile and an arm around my mom. My mom, sandwiched between us, has her head tilted up and her eyes straight ahead, with a smile that I see as defiant. She looks radiant to me, far younger than her 63 years even without the full head of hair that has defined her look for decades. It’s a picture I come back to whenever I feel thoughts of mortality creeping in.

If one day I do find myself with the same diagnosis, I’ll remember her strength and resilience and hopefully I’ll have a whole arsenal of protective factors to help me through. As I look at the photo now, I think about something else my mom said after her cancer treatment: “It’s been tough, but I’m stronger than I thought I was.” Though I doubt there’s a genetic test to prove it, there’s a good chance I am too.

Related:

I Am Turning Into My Mother (And I Feel Fine)

“Why Mother’s Day Is Now the Toughest Day of My Year”

I Can’t Stop Thinking About Moms Who Are Separated From Their Families—Like Mine Was

What’s Harder Than Being a Mom? Dealing With the All the Cultural Baggage That Comes With It