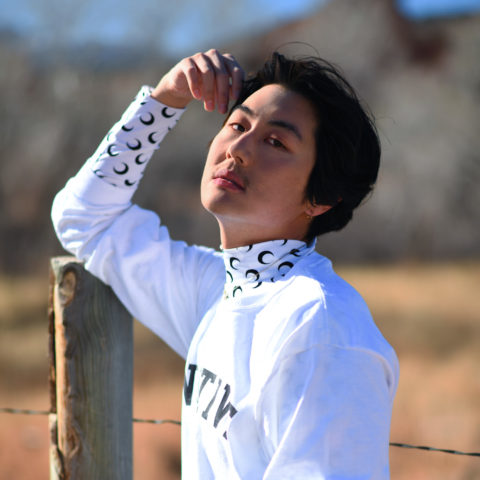

Good Light Founder David Yi on the Difference Between K-Beauty Appreciation and Fetishization

"Appreciate Korean cultures, stand with Koreans, and be an ally to us. As much as you love our beauty [rituals], you better love our people, too."

Multi-talented journalist, brand founder and author David Yi is a beauty industry powerhouse. With over a decade of experience under his belt in the New York media space (where he’s written for publications like WWD and Mashable), Yi launched his own inclusive beauty site, Very Good Light, in 2016. His latest ventures include a new genderless skincare brand called Good Light and an upcoming book called Pretty Boys (to be released June 22).

Kicking off our series of brand founder interviews for Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI) Heritage Month, we caught up with Yi to chat all things beauty, including why he’s launched not one but two inclusive beauty brands, and how consumers can appreciate Korean beauty without fetishizing cultural practices and rituals.

How did you make the transition from journalism to product development?

“I’ve been a journalist for over a decade, mostly in the fashion and beauty space, working for places like the New York Daily News, WWD and Mashable. Along the journey, I felt the beauty space was so gendered. For instance, why are beauty aisles so separated by the gender binary when there are, and have always been, more expressions of gender than just male or female? It also felt so alienating walking down both aisles knowing that neither catered to someone like me — a consumer who shaves but also likes to beat their face once in a while. One section is hyperfeminine while the other is hypermasculine, but I don’t think most consumers identify by either. It made me think there was room for more gender inclusivity and for the beauty industry to truly be a space for all.”

How did you first get into journalism?

“I started in high school at my school’s newspaper, The Lever. I always wrote about Asian American issues or centred my experience around being Korean American, which didn’t go down well with my editors. I remember one white woman editor telling me that they could no longer publish stories on Asians because they didn’t want to be labeled an ‘Asian newspaper.’ The xenophobia is real, folx. It made me realize that this person didn’t see Asians as Americans — and I had to fight for every single one of my stories to be published. It was an uphill battle but I’m so grateful for these experiences that truly prepared me for the hardcore journalism world in New York City.”

The democratization of beauty is a major pillar of your brands. Can you tell me why that’s important to you?

“I grew up in Colorado Springs as one of the only Asian Americans in a predominantly white city. I’ve always felt othered and as if I didn’t belong. There was also this notion that I wasn’t beautiful because of my almond eyes, my jet black hair, or my golden skin tone. Because I faced racism early on, it was essential for me to become an advocate and activist at a young age — to fight for others as well as for my own people. This early experience allowed me to feel a great sense of empathy towards others, and is the main reason I became a journalist. I wanted to tell stories from all perspectives and uplift others’ stories and their voices so they feel empowered.”

What has it been like launching a brand during the pandemic?

“It’s both rewarding and challenging. I was also simultaneously working on my first book, Pretty Boys, which is non-fiction and a deep dive into the history of men, masc-identifying folx and their relationship with beauty and power. I also worked on our campaign, BIDEN Beauty, which was instantly viral and raised funds for the DNC. I was so busy and distracted with productivity that I coped with my pain and anguish through suppressing it. I’m now decompressing, reflecting and also uplifting during this time. And healing — I’m definitely trying to heal.”

You’ve said before you never felt represented in the beauty community because you liked sheet masks and makeup, but also facial hair grooming etc. Can you elaborate on that and how Good Light addresses that duality?

“Good Light is a beauty brand that’s all about unleashing your own good light from within. First and foremost, it’s about self-actualization and love, self-worth and owning your beauty. If beauty is in the eye of the beholder, be that beholder. Only you can set the tone when it comes to power and agency. I hope that Good Light can continue being a safe space to explore who you are, your identity and your power. And we want to create products for all, no matter your gender identity, race, size, skin tone, skin texture, sexuality.”

What has it been like to witness so many Korean beauty rituals and practices become a part of North American beauty? Does it bother you to hear these practices be called “trends”?

“It bothered me when I was younger that Americans would discover other cultures and label them ‘trends’ as if we were discoveries for them to uncover. In reality, we’ve always been here. We’ve always thrived. We’ve always been beautiful; it’s just that others were slow to recognize centuries of our rich ancestry. While I am all about sharing cultures, I am not for fetishization or objectifying anyone based on their race or background. I love that K-beauty is democratized for all — it’s because Korean technology is the world’s best. But I am also for appreciating cultures as well. Appreciate Korean cultures, stand with Koreans, and be an ally to us. As much as you love our beauty [rituals], you better love our people, too.”

If Good Light was around when you were growing up in Colorado Springs, how would it have changed your approach to beauty? What would a brand like this have meant to you?

“It would have been so transformative. It would have been everything. To feel like seen, heard and validated would have meant the world. Representation matters — and I still cling onto Very Good Light and Good Light selfishly in times when I, too, need community.”

Growing up, what was your relationship to beauty like?

“I grew up with a Korean mother and father who both emphasized beauty products. My father would groom himself by slathering his pores with essences, toners and creams. My mother would do the same, inculcating to a young, impressionable me how important sunscreen is. I didn’t know this at the time but now after reflection, I understand how that was their way of coping against American racism and surviving through hardships. With every drench of their pores, they were practicing self-love. Five minutes every morning and night was a routine just for them, where they could quiet the world and be conscious, present and in the moment.”

What are your goals Good Light?

“My goals for Good Light are to continuing championing diversity, inclusivity and understanding that we have so much work to do! I’m rolling up my sleeves daily and seeing how I can help.”

What do you want the brand to say to people who feel like they don’t belong?

“I hope that Good Light portrays beauty beyond the binary. There’s so much power and beauty out there. We — collectively, all of us — are worthy and I hope this beauty brand shows that yes, a brand can give a damn!”