You’re not good at multitasking, you just think you are

It’s the middle of a Thursday afternoon and I’m lying on a mat in a chic studio overlooking Toronto’s posh Yorkville neighbourhood. Woodsy incense wafts through the air. My head rests on a pillow embroidered with an iconic image of Buddha. Phil, my meditation instructor, coaxes harmonic tones out of instruments called quartz crystal singing bowls. In calming dulcet tones, he suggests I let thoughts float in and out of my mind, like the incense in the air.

I’m at Helix Healthcare Group for my first mindfulness meditation class because, like more than six million of my fellow Canadians, I struggle with stress on most days. I’m a victim of multitasking—my brain is a whirring cyclone of thoughts, appointments, tweets and regrams. I’ve noticed something else troubling, too: At 35, I’m less able to focus on single tasks than I used to be. I forget things, like where I put my keys or why I’ve walked into a room. It’s a bit like a fog has rolled in.

I’m not alone in experiencing these premature “senior moments.” A U.S. survey conducted by research firm The Trending Machine found that Millennials are about twice as likely as seniors to misplace their keys or forget what day it is. “The easiest tie to brain fog would be stress,” says Dr. Catherine Sabiston, Canada Research Chair in Physical Activity and Mental Health. “In terms of brain health, stress and its impact on the body’s systems is the biggest issue facing young women right now.”

Heartened by research out of Harvard University that suggests mindfulness meditation can thicken the parts of the brain that control learning, memory and emotion, I start my own practice. My phone is powered down for the first time in ages and I’m ready for an hour of blissed-out nothingness. I take a deep breath in, exhale as instructed and—bam!—I’m hit with a rush of thoughts. Did I file an assignment with a typo? When will I have the chance to answer my emails? What if a client calls while I’m here?

Later I debrief with Helix’s clinical director, Jesse Hanson, and learn that this response is common for first-time meditators. “When we’re in a busy state of mind, we’re colluding with our anxiety,” he tells me. “The practice is to learn to watch those anxious thoughts and detach from them, rather than be fooled into thinking that we are our thoughts.”

Disconnecting from stress and anxiety seems like an impossible dream, yet it’s increasingly important for my brain function. When you face a stressful situation, your adrenal glands release a hormone called cortisol. This can be a good thing if you need to flee a burning building, but regularly steeping in cortisol and other stress-related hormones could put you at higher risk for myriad illnesses, from dementia to cancer.

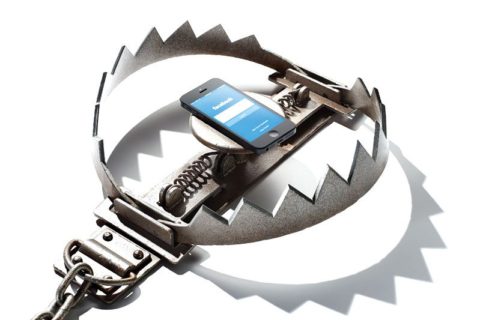

If stress is a big part of what’s causing my brain fog, my next step is to figure out what’s putting the pressure on. I’ll do that right after I post this pic and respond to this tweet and…wait, what was I writing? Oh, yes, a significant contributor to stress-induced lack of focus is the pinging from my purse. I love my phone and feel unmoored without it, though research suggests that the way we post, click and surf affects our mental and cognitive health. A recent big news story: Studies out of the University of Houston linked depression to how we compare ourselves to Facebook friends.

“Psychologically, loneliness is a negative symptom of the digital craze,” says Hanson, explaining that we deprive our brains of IRL human contact. “The part of our brain that has to do with the experience of connection is called the orbital frontal cortex…. Research suggests eye contact helps stimulate this part of the brain. When it fires, the person feels connected and not so alone.” So next time I feel compelled to connect with a friend via a kissy-face emoji, I’ll arrange a coffee date instead.

Taking my relationships offline is only one piece of the puzzle. The anxiety-inducing nature of my digital life extends to the mental habits I form when I spend my days swiping from Google to email to Twitter. While multitasking is seen as a virtue in our high-pressure lives, “We’re not good at multitasking, we just think we are,” says Earl Miller, a professor of neuroscience at MIT. “We can really only think about one complex thought at a time…. If you spend all your time switching between tasks, you’re wasting a lot of your brain processing time switching, not thinking.” Flipping from email to Instagram is so enticing, Miller explains, because the brain craves new knowledge. “We evolved to find information rewarding; where a rustling in the leaves might have been a tiger leaping out at us.” Knowing about an approaching predator is indeed life or death. Catching up on Gigi Hadid’s latest #OOTD? Not so much. When I shift from one task to the next, I seriously lose focus.

Luckily the brain is like a muscle I can change by adopting new behaviours. The solution, says Miller, is to limit my distractions. I follow his suggestion to quit my email, Facebook and Twitter while I’m working. It’s difficult to break my habit of constant checking, but gradually I feel less anxious doing challenging work.

This is the first step, but I’m curious about how my increasingly frenetic lifestyle may be affecting my brain in the long term. Dr. Cara Tannenbaum, a scientific director at the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, explains that lifelong learning is key to boosting brainpower and preventing cognitive illnesses like Alzheimer’s. “It may mean learning a new language or designing your own web page,” she explains. “It recruits different parts of your brain so your brain reserve is higher.”

I assumed that all my surfing was feeding my intellect, but what I read online may not be sinking in. “If you think of your brain like a computer, there’s what’s open on your screen and what you save. If you’re reading about Kim Kardashian and that page links you to a new YouTube video, do you press save at any point? No, you turn off your computer and it’s gone. You have to press save to use those brain cells.”

What better way to “press save,” I think, than to practise meditation? I set out to try again and, ironically, it’s a piece of technology that helps me understand how to focus my thoughts. I order Muse, a brainwave-reading headband designed by a Toronto-based neuroscientist/fashion designer. It uses sensors to send information about my neural activity to an app on my phone that gives me feedback about what my mind is doing while I meditate.

I slide the sleek-looking band onto my head. Five sensors press against my forehead and two more tuck behind my ears. I start a three-minute meditation session on the app and a soundtrack of a rainstorm starts playing through my phone speakers. The severity of the weather reflects my brain activity—the more active my mind, the more intense the storm becomes. Gradually I learn to control the audio cues: Focusing on my breathing yields a tranquil rainfall, while running through my to-do list whips up a tsunami. This doesn’t give me that blissed-out state I’m after—at least not yet—but I’m hopeful for sunny days ahead.