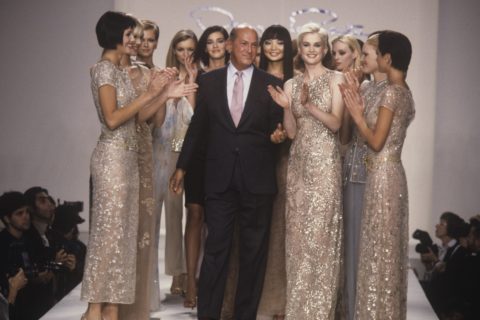

From the FASHION Archives: The Rich Essence of Oscar de la Renta from the Spring 1981 Issue

Behind a name known for luxurious garments, was a man known for grace

Since its launch in 1977, FASHION magazine has been giving Canadian readers in-depth reports on the industry’s most influential figures and expert takes on the worlds of fashion, beauty and style. In this series, we explore the depths of our archive to bring you some of the best fashion features we’ve ever published. This story, originally titled “Opulence and the Man” by David Livingstone, was initially published in FASHION’s Spring 1981 issue.

It used to be that Oscar de la Renta was known as an eminence in the republic of American fashion. Recently, his réclame has gone far beyond that, thanks to a cover story in The New York Times Magazine last December. Along with his wife Françoise, he became perhaps even more widely known as a mover is auspicious circles, a star of high society. It was impossible to avoid the impression given in the piece that the de la Rentas had no time for anyone less than the “very rich, very powerful and very gifted.” The implication was that Oscar de la Renta was some kind of operator, dealing friendship and trading on charm. In short, it put me on my guard at the aspect of meeting him.

“He’s very charming, very attentive – even if the most dreadful person in the world has him cornered.”

Of course, one of the most awesome things about the press is the way it can plant expectations and nourish attitudes on hearsay. Not that one didn’t have other reasons to wonder about de la Renta’s sincerity. I remembered that Jack Alexander, his administrative assistant, had once been reported as saying, “He’s very charming, very attentive – even if the most dreadful person in the world has him cornered.” Besides, in the advertisements used to launch his perfume in 1978, with the grateful model saying, “He’s been my designer and he’s been my friend,” it seemed the word “friend” had been thrown around a little loosely.

After only a few minutes on the premises of his thriving business on New York’s Seventh Avenue, aspects of de la Renta’s reputation are immediately verified. He is clearly familiar with the famous. Alexander is on the phone with a reporter who wants to know whether Nancy Reagan has bought anything there recently. (Though the First Lady is better known for wearing Adolfo and Galanos, she is the kind of customer one rightfully expects of de la Renta. After all, he is known to dress Nancy Kissinger.) And a casual glance at his secretary’s Rolodex index finds it open at the listing of a famous movie producer.

But besides this evidence, there is another, and possibly more accurate, clie to the nature of the man I am about to meet. Lying on the glass table in the office area just outside de la Renta’s studio is a seed catalogue. Trusting instantly that it belongs to him, I take it as a reassuring augury of his better nature. Blessedly, my intuition is corroborated by experience, and I only have to enter his studio and take a seat beside his desk to discover that his personal magnetism is genuine, not just some unctuous promotional device. Confronted simultaneously by the ringing of the telephone and my arrival, de la Renta immediately displays civilized priorities. Ignoring the machine’s racket, he says, “That’s alright, we can talk.” Contrary to preconceptions one might have about anybody who occupies a leading position in the beau monde, he shows none of the pushiness or edginess of the professional social climber always on the lookout for ways to take advantage. Rather, he is calm, personable, a touch bashful and entirely suave. Overall, his style is subdued. He is wearing a grey pinstripe suit (his own label visible on the inside pocket), a white shirt striped with a red that is deep enough to be discrete, brown belt and shoes, and as is his custom, a tie. Talking, he leans backward, not forward. His voice is softly accented, occasionally revealing his hesitancy in a stammer, Physically, his outstanding feature is his head. With greying curls combed back, his head’s symmetrical shape and and color, the result of Latin blood and recent sun, make it as pleasing to the eye as a brown egg.

Unavoidably, de la Renta’s attention must sometimes be divided. His assistants have questions. Garments are brought in from the sample room for his approval. His lawyer, Peter Tufo, is trying to reach him. But he apologizes for every interruption. Once, when he has to leave the room to attend to other business, he expresses his regret with a reassuring pat on my shoulder, and the gesture seems neither condescending, nor contrived. And when he has to take the phone, one is never made to feel like an intruder. In fact, I eavesdrop shamelessly. “Hello, Blassie? How are you? Happy New Year.”

Like Bill Blass, whom he regards as by far his closest friend among fellow designers, de la Renta emerged on the New York fashion scene in the ‘60s. Despite the success of earlier luminaries such as Norman Norell, Claire McCardell, Adrian, Pauline Trigere, American design was still thought to be innately, inferior to anything from Europe. It took a new generation, including Blass, Geoffrey Beene, de la Renta, as well as less enduring talents such as Rudi Gernreich and Jacques Tiffeau, to establish New York as a fashion capital comparable, in prices and prestige, to Paris. Foregoing the elitist couture tradition, they choose to be accessible and diverse, and become household names. Now, in addition to the main line of costly ready-to-wear, de la Renta is responsible for a lower-priced line, with the emphasis on day wear, that is made in Hong Kong and marketed under another label, Miss O. His licensing arrangements cover 18 product areas, including furs, men’s wear and, optical frames, sheets, perfume, jewelry, and jeans. There are also special licensing arrangements with specific stores in Mexico and Japan. Now, the retail volume of his ready-to-wear lines is $25-million; licensing arrangements bring in $250-million.

He fairly glows when he tells of the last time he was in Japan and Takanohana, a sumo champ and cultural hero, paid him the honor of attending his fashion show.

For all the many facets of his industry de la Renta is not given to fuss or panic. With a summer collection due to be shown in less than three weeks, he has just come back from his Christmas to learn that the fabric he was counting on is not going to be ready. His aplomb is almost unnerving. “This is the time when you have to be creative and do something else,” he says. “We have to scratch the whole program ad change the idea of what the collection will be.” Instead of badrapping the Japanese suppliers who failed to deliver the goods, he seems happier to talk about his fondness for that country and his passionate interest in Sumo wrestling. On the wall next to his desk, there are Polaroids that show him beaming in the company of some of those hefty, ponytailed athletes who In fact, were the inspiration for the printed fabric that didn’t arrive. He fairly glows when he tells of the last time he was in Japan and Takanohana, a sumo champ and cultural hero, paid him the honor of attending his fashion show.

On another wall of the studio hangs a collection of framed, front-page stories from Women’s Wear Daily that attests to his achievements at home. But even more impressive than the decor of the studio is the atmosphere. Three assistants work at separate tables, contentedly absorbed by the business at hand. There are also a student from the Rhode Island School of Design, who will be spending time observing and taking part in a top-flight design operation, and Isabelle Oduber, the model on whom de la Renta first his collections, who comes and goes wearing a smock, dark glasses and a bright smile. At lunch-time, food is ordered by phone, and the student welcomes the news that “the company pays for lunch.”

The mood of the studio seems to derive from de la Renta himself. He maintains a bustling pace while still managing a courtly quietude and never resorting to imperial airs. Although he has a high profile as a designer and socialite, he is, in person, completely unassuming. Asked about his Christmas holidays, he says, “I was in the Dominican Republic. That’s where I was born. I have a house there.” He appears completely unmindful that Vogue has devoted pages to a detailed description of his ocean-front villa or that the basic facts of his biography are matters of public record, unearthed with minimum research. He was born in Santo Domingo in 1932, has six sisters and a father who sold insurance and who was not overjoyed when his only son decided to be a painter and went to study in Madrid. Following the death of his mother, his father stopped sending money, and, to earn an income, de la Renta started doing fashion illustrations. Eventually, he found work at Balenciaga’s house in Madrid. While he says, “The first quality clothes I ever held in my hands were Balenciaga’s,” he conscientiously points out that the great Spanish courtier was based in Paris and the business in Madrid was run by his sister. When de la Renta himself went to Paris, he worked with another Spanish designer, Castillo, for three years. In January, 1963, he moved to New York.

To hear de la Renta say, “My sisters are all housewives. They have no aspirations of any sort”; to notice that a book called Harems is one inspiration for work on his summer collection; or to judge from his recurring forte, lavish evening wear, one might get the idea that he is only used to females in their passive modes. On the contrary, his career in the United States has been marked by associations with a variety of hard-working women. One of his first friends in America was Mary McFadden. Now a designer herself, McFadden at that time was doing public relations for Christian Dior, and she arranged for one of de la Renta’s first job interviews. But following the advice of another friend, Diana Vreeland, he finally accepted an offer from Elizabeth Arden to design couture for her company.

Elizabeth Arden, born in Woodbridge, Ontario, as Florence Nightingale Graham before turning into the legendary cosmetics tycoon, was not known for being fluffy. Notoriously difficult to work for, she showed de la Renta a more companionable side of her nature, inviting him to her house for dinners, when she would sport her favourite dress, a pink tea gown of Valenciennes lace over satin. The gown was worn to frailness, and, reciprocating her kindness, de la Renta made her a new one. “And when I used to go and dine, she still was wearing the old one. And I said, ‘You don’t like the tea gown I made you? It doesn’t fit? Well, it’s exactly the same.’ And she said, ‘Yes, I like it, but I’m waiting to wear it on a special occasion.’”

“Nobody understands dressy clothes better than Oscar de la Renta does.”

Elizabeth Arden was buried in her new pink tea gown. However, the women have favored de la Renta’s creations, appearing with his own label since 1965, have had livelier functions to attend. From the beginning, his extravagant evening costumes have appealed to the universal urge to get dressed up and go places. In 1967, he designed gypsy fantasies and won his first American Fashion Critic’s Coty Award; he won again in 1968 for garments inspired by Belle Epoque. In 1974, Women’s Wear Daily published a list of his customers which was largely comprised of prominent party girls. And in the approximately 82 garments shown last November for this spring, unrestrained luxury abounds. While there are surprisingly uncomplicated combinations of pants and middy-blouses (with subtly detailed yokes in the manner of historic Russian sailors’ outfits), harder to miss are the voluminous taffeta skirts, vividly coloured silk-satin organza dresses ruffled to the floor, bouncy lace blouses and opulent evening jackets with elaborate embroidery. These are clothes that announce themselves with bugles and castanets. Even when done in a delicate palette of pale blue and white, they are made for noticeable entrances. Show up at a darkened door in one of these, and doubtless you’d have them thinking that the summer sky had just dropped by.

“Nobody understands dressy clothes better than Oscar de la Renta does,” says Margery Steele, merchandising manager for The Room at Simpsons and an avid supporter. In Canada, retail prices of his garments range from $600 to $5,000, but, as Steele points out, there is never any trouble finding people to buy them, because “de la Renta understands the lifestyle.” He himself is used to the kind of occasions where grandstand chic is called for. Françoise de la Renta, her husband’s senior by nine years, now wears only his designs, though nothing says she has to and not everything coincides with her taste. “A lot of the clothes I design are not really for her, in the sense that she really doesn’t like to be very dressed up,” says de la Renta. She likes to wear very understated clothes, and a lot of my clothes are not very understated.”

Formerly editor of French Vogue, a contributing editor still fo American Vogue and a celebrity in her own right, Françoise de la Renta appears frequently enough in the pages of Women’s Wear Daily that, even without having met her, one can catalogue her preferences, usually expressed with an engagingly plain-spoken zest. She likes chocolate, never eats meat and doesn’t plan on plastic surgery. She is enthusiastic about food, and has so many sheets that she can go a whole year without seeing the same one twice. Though not extravagant in appearance – photographs typically portray her with hair drawn back and gathered neatly at the nape of her neck – she’s a disciple of sumptuous living. Invited to participate in a course called “Ultimate Chic,” given at New York’s Hunter College in 1978, she spoke to the class of the advantages of entertaining twice a week. That way, flowers and uncorked wine can be used up. And she once defined quality for W as “the best of anything – even a perfect potato.”

Although Françoise de la Renta is not directly involved in her husband’s business, the cover story in The New York Times Magazine took pains to depict her as a woman of influence. And there have been other public suggestions that she has determination for two. “If anyone hurts Oscar…I am like a tigress,” she told Women’s Wear in 1971, and last summer, when illustrator-turned-designer Michaele Vollbracht was all the news, W ran a Vollbracht caricature that depicted a puppet-sized Oscar on Françoise knee. The only sign I see of any role she plays in her husband’s affairs appears when de la Renta tells his secretary she doesn’t have to bother with hotel reservations in Washington for the inauguration. Françoise has made the arrangements. They’ll be staying with the Harrimans.

Back in 1967, when Truman Capote threw his legendary black and white ball, Vogue carried reportage by Gloria Steinem and the photographs included Françoise de Langlade” in pussycat masks. In the ‘80s, however, social life seems destined to be more serious and to rely more ostensibly on political forces. Until, Teddy Kennedy dropped out of the race, de la Renta supported Kennedy’s bid for the presidency. After that, he supported Reagan. “Arthur Schlesinger, a very close friend, made a joke about me and said I must be a very wise man to be able to make a 180-degree turn. The fact is, I’m really non-political. I vote because of the people I like and not really because of the party I belong to.” One person that he decidedly did not like was Jimmy Carter. In 1976, he told WWD, “I can’t stand that famous smile. I can’t stand it. There’s something about it – I don’t know – like a snake’s smile.” De la Renta grins when he’s reminded of the statement. Occasionally, as a designer, it has been suggested he is overly influenced by Europe, but there seems to be no question that, when it comes comparing Carter to a snake, he was the first on the block.

Like many in the fashion industry, de la Renta thinks that Nancy Reagan will be good for business. “The thing was, there was very little, fashion-wise, that you could do with Mrs. Carter.” Mrs. Reagan has worn de la Renta “from time to time,” and what’s even more significant, her spendthrift ways may be taken as some kind of official seal on the practice of conspicuous consumption from which all designers stand to profit.

He also speaks of the tropical flowers, of the strong colors that have influenced his “Latin eye” and of people whom he has not forgotten.

As clear as it is that de la Renta is no stranger to rich living, just as strikingly he reveals himself to be capable of enjoying more refined pleasures such as horticulture, friendship and music. During the holidays spent at his Dominican home an hour and a half away from Santo Domingo, he played tennis, planted a rose garden and tried to fatten up his cherished friend, Diana Vreeland, whom he describes as “the most fascinating fashion personality of this century. She made jokes about me forcing her to eat like a goose. And I said, ‘Not a goose, like a beautiful turkey.’” He also speaks of the tropical flowers, of the strong colors that have influenced his “Latin eye” and of people whom he has not forgotten. “The nice thing about going there is that a lot of my childhood friends have houses very close to me.”

No less affectionately, de la Renta praises the beautiful view of Central Park he gets from his New York apartment and he is never more becoming than when describing the white garden he has planted at his country home in Connecticut, where he spends every weekend. He likes to read, particularly biographies and 19th-century travel books. He enjoys opera and attends the Salzburg Festival every year. “I love really all the Spanish singers, Placido Domingo, a friend of mine, Victoria de Los Angelos, Montserat Caballé, Teresa Berganza.” And he is fond of good movies, no matter where they come from.

Discussing the article in The New York Times Magazine, he says, “I thought it was a very nice story. If I had written it myself, I would have written it differently. I think it showed one side of our lives. It tells really very little about ourselves as human beings.” Nowadays, the media, deferring to attention-grabbing angles, are not apt to provide subtle portraits. Customarily in stories about Oscar, Françoise has been used as the most provocative hook. She’s endured the kind of innuendo that Yoko Ono used to have to put up with, as if, even in these post-feminist times, there was something unseemly about a woman exercising power. Wisely, however de la Renta does not damage his dignity whining about being mistreated by the press. He seems perfectly happy being a star, accepting with elegance the price he sometimes pays for it.