Art or commerce? We zoom in on the explosion of designer video

Fashion Television (RIP) was ahead of its time in several ways, and here is one of them: In 1985, when executive producer Jay Levine launched the program, he imagined it might become a channel for short narrative videos about clothing. Fashion films, now so inescapable a phenomenon, were then just a thought without a name: if music videos could revolutionize the way we consume pop, couldn’t a little cinematography do the same for clothing? The ’70s had seen then-living legends Guy Bourdin and Richard Avedon experiment with the moving image, and as film-recording cameras became less expensive, it seemed likely they’d land in the hands of younger, emerging lensmen. As MTV was to music videos, so might Fashion Television be to this new mode of image-making.

It didn’t happen that way, though. Fashion Television burgeoned worldwide, becoming the Jeanne Beker–led interview and news program we loved so long (it ended—to the joy of nobody—in April). Fashion film, meanwhile, lay dormant through two more decades, until bang: YouTube. The video-sharing site was launched early in 2005 and by the time Google acquired it in 2006 for $1.65 billion, it had given music videos a second life. For fashion videos, it was more like a first life. And what a life. In seven years we’ve watched them go from Nick Knight’s living room to the very halls of Versailles (with a stunning Inez and Vinoodh video for Christian Dior Fall 2012). The medium has its own online compendiums, university courses and festivals; a television channel wouldn’t be nearly enough.

“When a designer produces a piece of clothing, it is to be seen in movement,” Knight told Penny Martin, editor-in-chief of The Gentlewoman, in an interview for his site, Showstudio.com, which has become the self-declaimed home of fashion film. In 2005, though, he was rightly hesitant to call it that. He had begun the two-year project Moving Fashion, commissioning not only photographers (himself, Tim Walker, Peter Lindbergh) but also models (Lily Cole) and editors (Katie Grand) to shoot 30-second clips of clothing in kinesis. “With the advent of the internet, the garment can now be shown in the way it was intended,” he said. “What I’m asking people to do is to express fashion in movement. It’s subtly different from asking someone to make a film.”

Those early Showstudio clips have original ideas but low budgets and poor production values, making some feel as dated as Robert Plant videos. Compare them with the seminal “By a Waterfall” scene from Busby Berkeley’s 1933 film Footlight Parade, in which synchronized swimmers clad in maillots and swimming caps float slowly into zipper formation. Berkeley was keenly aware of fashion, and must have been delving into film while Elsa Schiaparelli was evolving with zippers. When you isolate that scene, it becomes an early example of fashion film where “film” is the operative word. Transcending costume, a story is told.

Without that illusory narrative quality, without plot and fiction, fashion films are really just commercials. And as brands from Prada to Wonderbra caught on in the mid-’00s, that’s what they quickly became. The Dior video, shot by Inez and Vinoodh with a series of supermodels at Versailles, is a consummate example. The women come and go. They wear Dior. But where do they go? Do they talk of Michelangelo? Who knows, and frankly, who cares? It is the most beautiful commercial and it represents to some the pinnacle of fashion, but it’s by no means a film.

Then again, if you consider that the imperative of any designer or brand is—spoiler alert—to sell clothes, even the most filmic fashion shorts are ads. “Commercials are probably no longer than 30 seconds. [Fashion films] are commissioned and normally have a larger budget with certain restrictions dictated by the brand,” says Diane Pernet, founder of the website and fashion film festival A Shaded View on Fashion. “Aside from that, there is no real difference.”

Still, Pernet says that in planning the festival, which she founded in 2008, she chooses films for their adherence to traditional cinematic values. “I want to be captivated by it within the first few frames,” she says. “I expect to see arresting images, acting not posing, great sound design and excellent art direction. A fashion film that follows the same general principles as any other film is a good start—with the exception that fashion has to play the role of the protagonist.”

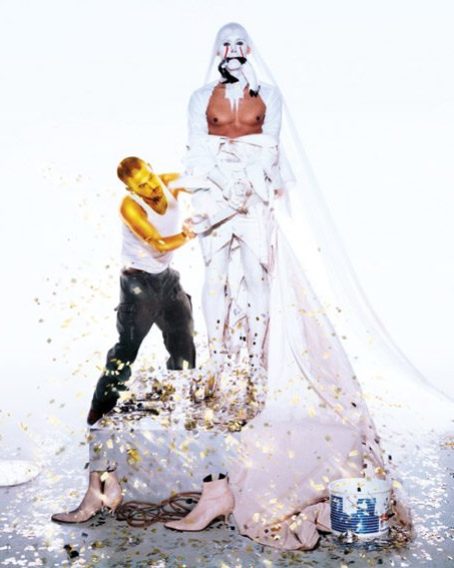

It’s reductive to say that film tells stories while fashion merely sells products. A fashion film can do both and still be called a film, as long as its protagonist—the costume—feels like a real, living, moving thing. Consider on one side the everywhereness of product placement, to which we’ve become inured, not only in mainstream but also “indie” movies and TV shows. Consider on the other the portfolio of original, exclusive “content” on Nowness.com, which is owned by luxury conglomerate LVMH but run as an independent editorial site. The site is famous for its fashion films: Ryan McGinley’s butterfly symphony for Edun; Steven Sebring’s poetic boxing match featuring Patti Smith for Reed Krakoff. They have fleshy narratives and instigate feelings. Still, as you click through the site’s categories, you’ll note that fashion films are listed under fashion, not film.

That may change. More established filmmakers—David Lynch and Sofia Coppola for Dior, Harmony Korine for Proenza Schouler, Roman Polanski for Prada—are getting into fashion film and inspiring a younger set to experiment, the way auteurs such as Spike Jonze used to with music videos. “When a medium is as new as fashion film is, it takes a while to feel it out and see what works,” says filmmaker and Bad Day Magazine editor-in-chief Eva Michon. She has expanded from music videos into fashion videos, directing clips for Canadian designers and brands such as Calla Haynes and Pink Tartan. “The expectations are higher as people tire of superficial videos and filler content,” says Michon. “Fashion brands have the money and recognize the importance of being viral. With designers doing up to four collections a year, that’s a significant opportunity for a director to develop a vision while getting paid for it.”

Fashion designers, meanwhile, realize this is a two-way runway. Tom Ford’s 2009 directorial debut, A Single Man, was a fine meditation on beauty and death in which clothing, or self-fashioning, was integral. Yohji Yamamoto and Rad Hourani are both working on their first feature films. If more designers step out of the wardrobe department and into the director’s chair, we might see fashion define film as it did in the gone days of costume greats such as Edith Head or Gitt Magrini. It would be welcome. Garments have long been characters in our lives; we’re only now beginning to tell stories worthy of them.