The Death of My Poh Poh Made Me Wonder: How Do Chinese Families Deal With Grief?

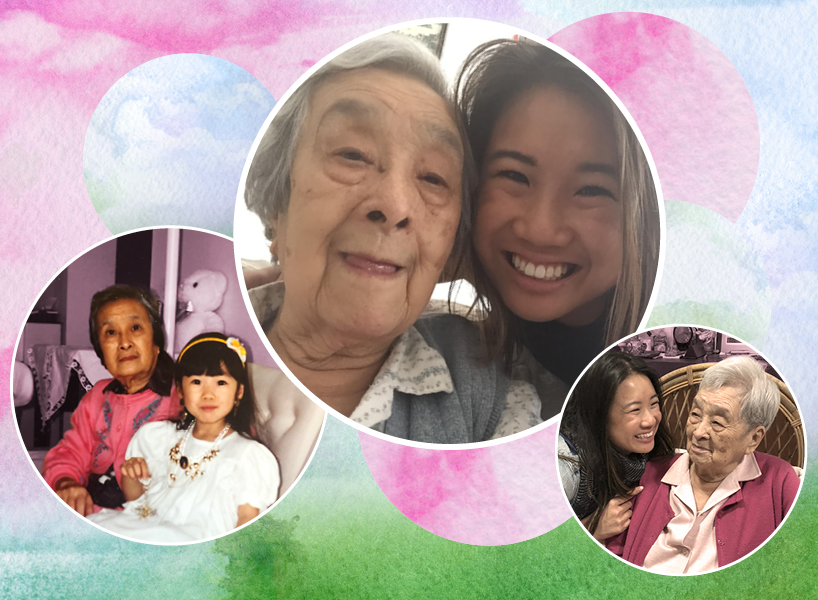

When her grandmother passed away, Madelyn Chung was confused by her family’s reaction—or lack thereof

It’s been a year since I saw my grandmother for the last time.

My beloved poh poh (Chinese for maternal grandmother), who lived on the tiny island of Mauritius, had been having health problems for three years, so, knowing she might not be around much longer, my mother and I decided to visit her.

I’ll never forget the last moments I had with Poh Poh. After dinner, she sat in her chair in front of the television and I sat beside her and held her hand, stroking her soft skin, with a feeling of dread: I was about to say my final goodbye to her. Later, as we packed our things into the car before heading to the airport, my grandmother came outside to see us off despite it not being safe for her to walk on her own. I could feel my heart breaking; it was as if she too knew that we would not see each other again. We took her back inside, and I kissed her goodbye one last time.

She died two months later.

The time immediately following my poh poh’s death was strange and stressful. It was the first significant loss I had experienced, and I felt heartbroken. As my mother told me the news, she was, understandably, grief-stricken, and it was difficult for me to see the woman who I considered to be the epitome of strength break down into tears. But after that, my mom internalized her feelings: She didn’t show her grief, nor did she express it verbally. And my father didn’t show much empathy, telling me there was no reason to be sad because my Poh Poh had lived a long life.

I felt isolated and unsure of how to cope with my feelings, and I was afraid to speak to anyone in my family about it because, well, they generally aren’t ones to show emotion let alone talk about it. All I wanted was to process my grief with the people who were going through it at the same time, but for some reason no one was talking about it. A friend of mine, who is white, had lost her grandfather a week before I lost my poh poh. She told me that spending time with her family and talking to them about her grandfather’s death was what helped her with that loss—which made me wonder why my Chinese family couldn’t do the same.

Talking about death is hard enough, but cultural traditions can make it even more complicated.

Part of my fear of talking about the death of my poh poh came from my Chinese family’s aversion to talking about death in general. I remember being told by relatives from a young age that the number four was unlucky because in Chinese the word for it sounds very similar to the word for “death.” The word “death” is extremely taboo in Chinese culture as it is believed that death will come if it is mentioned. Many Chinese people (my family included) go to extreme lengths to avoid the number four on their license plates, house numbers and phone numbers because of this superstition.

And this isn’t the only way the Chinese tiptoe around death. Some refuse to register as organ donors or write their own wills for fear of cursing themselves and bringing on death. It’s also not uncommon for family members to conceal the death of loved ones from their elders as they believe the shock would be too distressing for them, and Chinese doctors often break bad news to family members rather than to the patients themselves.

The latter can be seen in Chinese-American director Lulu Wang’s latest film, The Farewell, which tells the story of the aftermath of her nai nai (grandmother) being diagnosed with advanced lung cancer. The doctor reveals the news to Nai Nai’s sister, who then decides that it would be best to keep the diagnosis from Nai Nai in order to prolong her health as much as possible.

Crazy Rich Asians star Awkwafina plays the role of Billi, who is based on Wang herself. Like her character, Wang had emigrated from China to the United States at a young age and didn’t have anyone to share her first-generation perspective of her family’s decision to keep Nai Nai’s illness from her. At one point, Billi’s mother (Diana Lin) chastises her daughter for suggesting that she be more sensitive about her dying mother-in-law, saying, “What do you want from me? To scream and cry like you?”

That scene struck a chord with me, as I had also been criticized by my family for being too emotional. I have always been the one who cries too much, feels too much and expresses feelings too much. For years I felt as though there were something wrong with me, that I was weak, because I couldn’t suppress my emotions like the rest of them.

“Grief is usually dealt with in the private space of homes,” Wang tells FLARE. “I think that in Western culture there’s a level of stoicism, whereas in Eastern culture it’s more about saving face. And both might look the same, but they’re very different concepts.”

The expression of grief is related to other aspects of culture

My family’s aversion to expressing their feelings is typical of Chinese families. Traditionally, Asian cultures place great value on the family as a unit and are collectivist by nature. Bringing honour and not shame to the family is of utmost importance, which is why Asians are often expected to suppress rather than express their feelings. In fact, it is typical for Chinese people to express their condolences with a saying that translates to “I hope that you will restrain your grief and adjust to the change.”

“Traditional Chinese culture discourages emotional expression probably as a way of ‘saving face,’” says Professor Jon K. Reid, a board-certified counsellor who has taught grief and loss courses at Renmin University of China in Beijing. “What I think is a related issue is the reluctance to say ‘I love you’—there’s a preference for ‘I like you.’”

Having been born and raised in Canada, I found my family’s reaction to death bizarre at first. In film and television, I’d always seen Western families bond over grief and find comfort in each other during those difficult times. But that doesn’t mean my family’s way of grieving was wrong. Andrea Warnick, a Toronto-based registered psychotherapist and grief counsellor, says that there are many ways to deal with grief.

“There are so many people who, based on the way they are wired, grieve in very different ways,” she says. “A lot of times, more verbal people are going to express themselves through talking, whereas some people are far more cerebral and it’s more of an intellectual process as opposed to an emotional one.”

Perhaps the Chinese process grief through rituals

When I was fairly young and relatives died, I don’t remember having a discussion with my family about the death, but I do remember the rituals we had to follow when it came to the wake and funeral. There are a few things that stand out in my memory: receiving a red envelope containing money (for luck, as death is a bad omen) and a white envelope containing candy (to sweeten the taste of death), bowing three times in front of the casket (to pay the highest respects to the deceased) and showering immediately when we got home (to cleanse ourselves of anything that has to do with death).

Historically, many different cultures have used rituals to deal with grief, says Warnick. “We use rituals to guide us through the hardest times in life, and part of their purpose is that when we’re struggling the most, we don’t have to figure out ‘Okay, what do we do next?’ We have rituals in place that guide us through,” she says.

Chris K. K. Tan, an anthropologist at the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences at Nanjing University in China, says the main purpose of mourning rituals is to “allow the bereaved family to mourn the passing of the deceased in a dignified manner.”

He adds that the emphasis on dignity comes from the focus on rituals in Confucianism. “[Confucius] advocated moderation and using ritual to limit the possibilities of over-indulgence,” he explains. “When it comes to funerals, the immediate family of the deceased must express their grief, but not to such a degree as to lose one’s comportment.”

Acceptance and understanding are ultimately what’s important

I have yet to have an in-depth conversation with my mother about Poh Poh’s passing. I took her to see The Farewell and realized right before that the subject might cut close to home. A part of me panicked. Did I really want to enable that catharsis and see my mother break down again? Another part of me wondered if this would be the thing that would finally get us talking about it.

Spoiler alert: It didn’t. She acknowledged afterward that it was an excellent film, but she remained composed throughout while I sobbed uncontrollably when Billi said farewell to her nai nai. Later, when I attempted to speak to her about grief and whether she’d spoken to her siblings about their mother’s death, she simply said: “We don’t really talk about these.”

The death of my poh poh was one of the hardest things I’ve experienced, but, in a way, her passing allowed me to learn more about myself, my family and my culture. I’ve realized that though they may not express their grief in ways that seem natural to me, it doesn’t mean that it’s not right—they’re just doing it in their own way.

Related:

By the End of The Farewell I Was an Emotional Wreck—and Not Just Because It’s Sad

This Is Us Shows How Grief Isn’t Something You Just ‘Get Over’

Where to Find Affordable & Accessible Mental Health Care Across Canada