Dior Collaborated with Grace Wales Bonner and a Number of African Artisans For Their Cruise 2020 Show

Our critic reviews the Dior Cruise 2020 show in Marrakech.

Earlier this month, the New York Times published an article titled “Finding the Beauty in Cultural Appropriation,” which sent a reflexive cringe shuddering through my body. Not another article excusing clueless white girls for wearing war bonnets, I thought, as my eyes rolled further back into my head than they ever had before. But after scrolling through what I initially assumed would be a hate-read, I was quite taken by the author’s thesis that the impulse to look toward experiences outside one’s own is innately human and we would do well to understand what that means as opposed to dismissing the instinct outright.

This story was the first thing to float through my mind after viewing images of Maria Grazia Chiuri’s Cruise 2020 collection for Dior, which was rife with jumpsuits, tailored jackets, head wraps and even a few gigantic capes à la André Leon Talley made out of Dutch wax fabric. The vibrant, often arrestingly beautiful textile bears a complicated history. The gregarious patterns, now synonymous with the clothing of West Africa, once belonged to textile producers of Indonesia, and was brought to the continent by the region’s Dutch colonizers.

Though it initially seemed a bit strange for a couture house to anchor a cruise collection aimed at the globetrotting elite with a hardy fabric that trails a sordid history of colonization, this was not a simple case of appropriation. Vogue Runway described the collection’s theme as “luxury, globalism, and culture,” noting it came to fruition thanks to a collaborations with a number of African designers and artisans, as well as Black artists and designers like Grace Wales Bonner and Mickalene Thomas.

Uniwax, one of the last remaining factories to produce Dutch wax prints using artisanal techniques, was tapped to create much of the fabric used in the collection. Sumano, a women’s textile and ceramics association in Morocco, contributed the long fringed duster jacket that opened the show. Monsieur Pathé’O, a designer from the Ivory Coast known for making Nelson Mandela’s shirts, contributed a look with the leader’s face on the back.

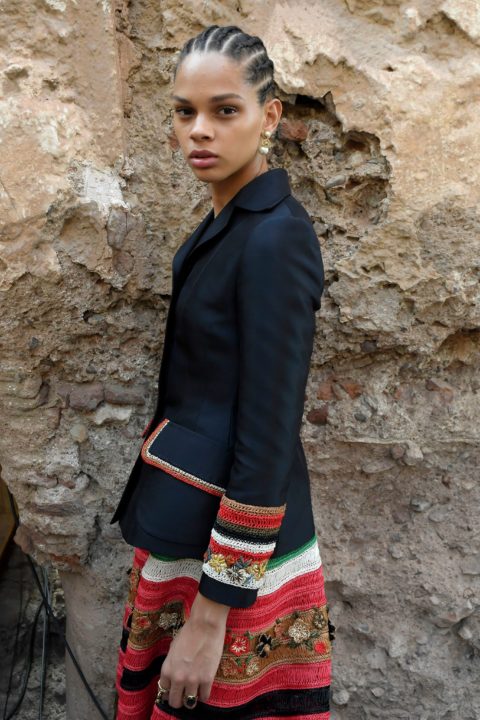

British designer Grace Wales Bonner reinterpreted the classic Dior Bar jacket and New Look skirt, keeping the smart silhouette but adding a colourful crochet trim. (“For me, it’s kind of reminiscent of Caribbean domestic craft techniques. I was interested in representing something that is emblematic of European luxury, but then also embedding a different cultural perspective within that…It was about creating a hybrid of two things,” Wales Bonner told Vogue.) African-American artist Mickalene Thomas (whose work was recently exhibited at the Art Gallery of Ontario) was also tasked with reinterpreting the Bar jacket. Her version incorporated small squares of patchwork fabric and Murano glass beads to create a jacket that was both delicate yet down-to-earth in its beauty.

“Today fashion is not only clothes: it’s a moment, it’s an experience,” Grazia Chiuri told WWD. And what she presented left her audience in awe. Susie Bubble posted a long tribute on Instagram stating, “This was the “Africa” collection to atone for all the other “faux-Africa” collections hailing from Western fashion brands that came before.” “Years…from now when the four fashion capitals no longer exist or have moved, and the axes of mainstream culture have shifted to continents beyond USA and Europe, we will talk about this Dior Cruise show and its ambitious endeavour to bridge cultures, and truly be inclusive, not just in terms of casting but in the formation of the collection,” she wrote.

The success of Dior Cruise 2020 hinges not just on respectful collaboration but its willingness to accord Dutch wax fabric the respect it deserves. Traditionally, Dutch wax is fashioned into loose-fitting tunics and voluminous bottoms where the main point of visual interest is the pattern as opposed to the garment. By using Dutch wax as the base for a series of exquisitely tailored suits, the fabric was placed in conversation with couture techniques that only served to make it more beautiful. The refusal to relegate the fabric to simple silhouettes acknowledged rather than obfuscated the painful history of the textile and served as an apt metaphor for the complicated history of cultural appreciation vs. appropriation.

The only misstep in the entire collection was the use of military camo patterns, which felt a touch out of step considering the number of brutal military dictatorships that have played out in many countries on the continent.

According to Connie Wang, the author of the New York Times article, “determining when cultural appropriation is O.K. can feel as if it requires a delicate calculus, more holistic than binary.” It appears Maria Grazia Chiuri managed to get all her calculations right.