Here’s How to Talk about Sexual Assault Allegations When It Comes to Your Favourite Celebs

Because what you say—or tweet—matters

*Trigger warning: This story contains descriptions of sexual assault.

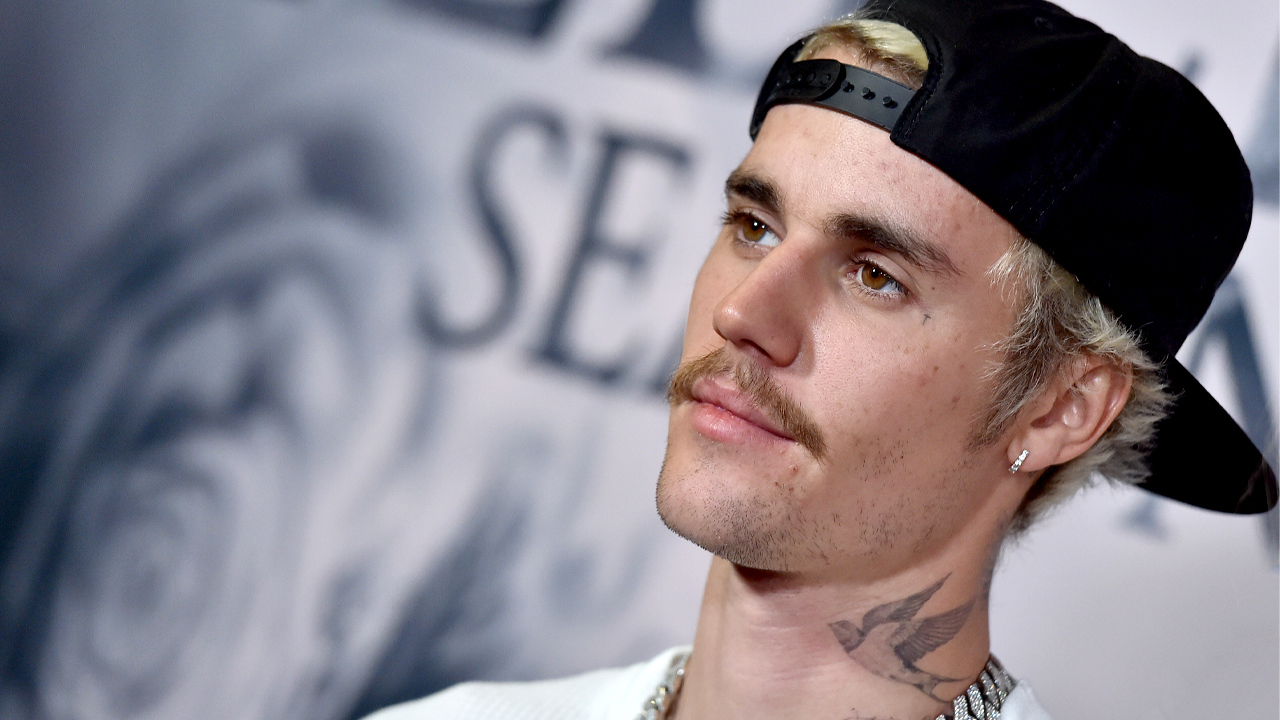

On June 21, Justin Bieber took to Twitter to address some recent, and very serious, sexual assault allegations against him. In a now deleted tweet from June 20, a Twitter user named Danielle claimed that the Canadian singer sexually assaulted her on March 9, 2014 after a music event in Austin, Texas, alleging that after performing a surprise set, Bieber invited Danielle and her friends to the Four Seasons hotel, where he took her to a separate room and assaulted her. The Twitter account associated with the tweet has since been deleted. In a series of tweets, Bieber denied the allegation, saying that while rumours are rumours, “sexual abuse is something I don’t take lightly.”

Rumors are rumors but sexual abuse is something I don’t take lightly. I wanted to speak out right away but out of respect to so many victims who deal with these issues daily I wanted to make sure I gathered the facts before I made any statement.

— Justin Bieber (@justinbieber) June 22, 2020

The singer then provided what he says are “receipts,” showing his whereabouts on the days in question—including articles and (actual) receipts that indicate Bieber was in Texas at the time with then-girlfriend Selena Gomez and stayed in an Airbnb with friends.

The allegations against Bieber came the same day actor Ansel Elgort was also accused of sexual assault by a former fan. In a June 20 tweet (that has since been deleted), a woman named Gabby alleged that Elgort—known for Baby Driver and The Fault In Our Stars—raped her when she was 17-years-old. The details in her account are incredibly upsetting. Gabby claimed that she met Elgort in 2014 after messaging with the actor on Snapchat, two days before her 17th birthday. Gabby says that Elgort was aware of her age (the actor would have been 20 at the time). During a sexual encounter, Gabby claims that she was “sobbing in pain” and Elgort made cruel remarks. “I have PTSD,” she wrote of her life now. “I have panic attacks. I go to therapy.”

On June 21, Elgort addressed the allegations made against him on Instagram, posting a notes app-esque explanation and stating: “I have never and would never assault anyone. What is true is that in New York in 2014, when I was 20, Gabby and I had a brief, legal and entirely consensual relationship. Unfortunately I did not handle the breakup well. I stopped responding to her, which is an immature and cruel thing to do to someone…As I look back at my attitude, I am disgusted and deeply ashamed of the way I acted. I am truly sorry. I know I must continue to reflect, learn and grow in empathy.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/CBrc56ABpWn/

While many people in the comments of Elgort’s apology *did* call out the actor for gaslighting and what comes across as a pretty insincere apology, many of the actor’s fans were vehemently sticking up for the former teen heartthrob, attacking Gabby and deciding that she’s lying. “Ansel would never ever hurt a girl. Id put my kidneys against her word,” Instagram user @barkayeezus commented on Elgort’s apology.

Similarly, in Bieber’s case, some fans responded disparagingly towards the accuser, saying: “A poorly written fanfic lmao,” and “bros like one of the most attractive people on the planet why would he do that lol.” And, folks, we have a problem. Because how we engage with survivors and their sexual assault claims is important—regardless of whether or not it’s your fave celeb at the centre of the allegation. Here’s how to thoughtfully engage with allegations—and sexual assault discourse—online.

First of all, experts aren’t surprised by fans’ responses—for several reasons

While some online may have initially been taken aback by fans’ reactions to these claims, Zanab Jafry, a Toronto-based Sexual Violence Specialist, wasn’t particularly surprised—because it’s indicative of our current society, she says. ”As of right now, our entire society is based in a rape culture,” Jafry says. As human beings, Jafry continues, we currently exist in a culture that is pro-rape and that enables sexual violence on every level. “[In North America], our criminal justice system remains unfit to deal with sexual violence, our healthcare system propagates sexual violence by limiting care to marginalized populations, our welfare system and our education system propagate sexual violence in their own rights (by limiting support to people who need it the most, creating situations for vulnerable people to become more prone to sexual violence through placement in foster care etc, and limiting resources to address the full spectrum of sexual education needs, respectively),” she continues. “And so it would be unsurprising for any community, including those that define themselves as fans, to respond this way because all of us are a reflection of the culture that we exist in; and because we exist in a rape culture, it would make sense that a fandom would respond in line with that culture. I don’t see that as being an anomaly—I think it’s simply a reflection of the times that we currently exist in.”

And not to mention, as Gemma Broderick, the executive director of Durham Rape Crisis Centre in Oshawa Ont., says, this reaction is something we’ve seen before when it comes to celebrities and sexual assault—time and time again. “I’m not surprised because we’ve seen this with the Me Too movement,” she says. Over the past few years, celebs like R. Kelly, Chris Brown and Hedley’s Jacob Hoggard have all been accused of sexual assault—and while some, like Kelly and Hogard have faced certain legal consequences—all three have also been vocally supported by fans—many of them female. “It speaks to the level of social capital and power that these celebrities have,” Jafry says of this undying support for our celeb idols. “I think it also creates a sense of immunity as well for some of these celebrities because they know they have such a wide following; they can rely on rape culture to paper over instances of harm that they’ve caused in the past. So there’s also a sort of herd immunity that comes with having a fandom that is so strongly on your side.”

Despite the fact that the latest reaction from Elgort’s and Bieber’s stans isn’t unusual, that doesn’t make it any less harmful. For Broderick, one of the main concerns she has with fans’ reactions and comments disparaging these women is the inherent judgment or determination of how believable their claims of sexual assault are. “It takes a lot of courage for someone to come forward about sexual violence,” Broderick says. And while she says that people may be confused by or not understand why a survivor would come forward months or even years after the alleged assault, seeing comments disparaging or denying their account can be extremely harmful. “This is just re-traumatizing them,” she continues. It also inherently puts the blame *on* the victim, which can lead to further trauma. (And, FYI, it’s no one on the internet’s place to determine whether or not an account is credible.) “It’s concerning when other people are weighing in and saying whether it’s true or a lie,” Broderick says. “Victim-blaming is something that just can’t happen.”

For fans—and anyone—it’s important to be aware of what you’re putting out there

Really, everyone needs to be aware of what they’re saying online—and how that might affect survivors. Especially because, thanks to the internet, what we say online can and typically does have a lasting reach and effect. For Jafry, the fact that all three aspects of these celeb encounters—the individuals reporting sexual violence, as well as the responses from the fandoms and alleged perpetrators—happened on the same website is interesting. “It speaks to the fact that social media plays a couple of different roles, as both a pulpit as well as an echo chamber,” she says.

What this means is that people typically use social media in one of two ways. “[Some] people use it to reach a wide audience, potentially billions of people; whereas you have other folks who may be treating it as a way to express their thoughts into the abyss without so far as thinking who is reading this and how is it impacting them,” Jafry says. And while it may be easy to think that responding to an allegation or tweeting your thoughts and judgment on a situation holds little weight—the truth is that our social media presence is *heavy*. And what we tweet and say can have repercussions beyond our own timeline. “I think recognizing and ascribing real value to our words is a good starting place,” Jafry advises to fandoms—and anyone engaging online with sexual assault. “When it comes to approaching some of these allegations of sexual violence, we need to ascribe a lot of value to what we’re saying, so as not to fall into the trap of thinking: ‘Oh, this is my Twitter account. It’s an echo chamber and I’m simply expressing myself.'”

Because it’s not just potentially affecting the individuals directly involved in the claim, but also could be affecting other survivors on social media. “We need to remember that [globally], one in three women [and] one in six men will be affected by sexual violence at some point in their life,” Jafry emphasizes. “And that means that inevitably, we are surrounded by survivors all the time. It’s inevitable that a survivor is going to come across your tweet. It’s inevitable that a survivor is going to read your Facebook post. It’s inevitable that they’re going to hear your thoughts about sexual violence and how it should be dealt with. So as members of our respective communities, what kind of role do we want to play moving from rape culture to consent culture, [and] do we want to be encouraging of survivors?”

And not only encouraging of survivors who speak out, but also to those who may not have spoken out and are considering doing so. Roughly, only one in 10 people ever come forward with sexual assault complaints. “So that means nine out of 10 choose not to,” Jafry says of reporting. “If we ever want that statistic to change, I think we need to be very careful with the kind of thoughts that we put out there with great care, not only for ourselves, but also the people who are going to be reading it; [because] it’s very possible that someone might come across our tweets and be either encouraged or discouraged to share their sexual violence stories and what happened to them.”

Jafry’s advice: “Before we say anything at all, just assume that there are survivors in the room. [Ask yourself] what am I about to say and how is it going to impact the people in this room?”

We need to reframe the way we think about accountability—and celebrity

Another thing to consider before engaging with discussions about sexual violence in relation to your celeb faves is the way that we as a society view accountability—which is entirely in the negative. Often, when our faves are called out for instances of harm, fans can be quick to defend them, saying that they don’t “deserve” this punishment (an argument especially utilized if said person was younger when the incident occurred). “In rape culture, accountability is seen as punishment, it’s seen as denigration and it’s really seen as a negative thing that we all have to run away from,” Jafry says. “If we are held accountable, [it’s seen] that something very, very bad is happening to us or we’re losing something by being held accountable.” But, she urges everyone—not just people in fandoms—to re-consider how we view accountability. “As we move from rape culture to consent culture, we need to reframe accountability as care,” she says. “So to hold someone accountable is to truly care for them.” And the rational makes total sense. “If you don’t care about someone, you wouldn’t want them to improve, [but] when you do care about someone, when you do value their work, when you do value who they are as a person, you want them to constantly be improving. So if you truly care about the celebrity or role model, you would want them to do better in the future. And that begins by rectifying the harm that we’ve caused.” So, instead of shying away from accountability or moving into denial mode to shirk it, Jafry advises reframing accountability as a kind of care that you’re showing someone you deeply respect.

But also, interrogate where that sometimes blind respect for celebs like Bieber and Elgort comes from. It’s no secret that celebs are often held above the law, especially when it comes to sexual harm. As University of Chicago law professor Martha C. Nussbaum stated in a January 2017 article for HuffPost, we as a society have created “a class of glamorous and powerful men,” who are above reproach. According to Nussbaum: “These men will almost always prevail against all accusations, no matter what they do in the sexual domain, because they are shielded by glamor, public trust and access to the best legal representation.” And while the latter inevitably helps, in many cases, it’s the sense of public trust and glamour that does the most shielding. Just look at people like former comedian Bill Cosby and still-working director Woody Allen—two men who have been accused of sexual assault for *decades.* While Cosby is finally serving time in prison, Allen continues to work with high-profile actors; and is respected for his body of work, despite the fact that much of it seems eerily similar to the allegations of harm in his personal life.

“I think that what we all need to do—and not just fandom, but as a whole community—we need to really reframe the way that we look at celebrities as members of our community and in our society,” Jafry says. While their influential power does have the ability to enact positive social change, at the same time, they also have a responsibility as people with immense social capital. “They also have a large following, they often have advantages and money; all of these things present the possibility for abuse of power,” Jafry says. When you have power, there’s the opportunity for abuse of power. And when that power and capital is abused? “We see situations like the ones that are unfolding with Ansel Elgort,” Jafry says. “In that situation, there is an abuse of the power that he had with regards to age, with regards to his social capital [and] really relying on his following to kind of paper over the situation.”

Jafry says we should try to see people like the Biebs, not as idols that can do no wrong, but rather, as creators of art that we can respect, care about and value, while still holding them accountable for their personal actions. And for young fans, she emphasizes the importance of recognizing sexual violence as not just an individual incident where consent isn’t given, but also as an abuse of power more generally. “Sexual violence can’t exist without a power imbalance,” she says. “That could be money, for example, if someone is using a lack of funds to coerce someone to do something. But similarly, life experience or age, that’s also power. It is always the responsibility of the adults in the room to make good and right decisions. And age gaps in relationships are not just obstacles to overcome, but they are actually huge imbalances of power that may lead to and contribute to sexual assault.”

And continue to believe survivors

And most important, it’s vital that everyone both online and IRL continue to believe survivors. To his credit, in his Twitter responses to the allegations against him, Bieber highlighted this fact, tweeting: “Every claim of sexual abuse should be taken very seriously and this is why my response was needed.”

Every claim of sexual abuse should be taken very seriously and this is why my response was needed. However this story is factually impossible and that is why I will be working with twitter and authorities to take legal action.

— Justin Bieber (@justinbieber) June 22, 2020

But in the same tweet, Bieber *also* stated: “However this story is factually impossible…” It’s a dichotomy that may lead people to be confused by and question what it truly means when advocates say “believe survivors.”

For Jafry, understanding what is meant when people say “believe survivors,” requires us to take a step back and look at the bigger picture. Often, when these situations arise, we treat them individually, but we need to start thinking about a collective default that prioritizes the well-being of the survivors. “I think it’s more useful to look at it in terms of a culture shift,” Jafry advises. “When we say we ‘believe survivors,’ [it’s important to] look at: What is the future that we’re trying to build? We’re trying to build a future where we believe people have been harmed when they say that they’ve been harmed, and we do this because we have the intention of providing them with support.”

“We are all members of a community that is trying to build a consent culture,” Jafry says. “I think that’s where people get messed up or where they find themselves looking too deeply into discrepancies or details [in individual cases]. The real bigger picture is what’s important in this situation, is that when we say we believe survivors, we’re trying to build a world where people who have been harmed can come forward safely.”

Broderick agrees: “It doesn’t matter what happened,” she says. “It just matters that it happened; and people need to believe survivors and help support their journey.”

Are you currently experiencing or have experienced sexual violence? If you are in immediate danger, call 911. For those unable to or who feel uncomfortable obtaining assistance from law enforcement, visit The Assaulted Women’s Hotline for 24-7 support (Ontario-wide). For additional resources—and ways to help survivors of sexual abuse—in different provinces, visit: Association of Alberta Sexual Assault Services (Alberta), Wavaw Rape Crisis Centre (BC), Klinic Sexual Assault Crisis Line (Manitoba), Sexual Violence New Brunswick (New Brunswick), Newfoundland and Labrador Sexual Assault Crisis Line, Break the Silence (Nova Scotia), Ontario Coalition of Rape Crisis Centres, Prince Edward Island Rape & Sexual Assault Centre, The Montreal Sexual Assault Centre (Quebec) and SASS (Saskatchewan).