Black Is King Is Coming—But Not Without Controversy

Some fans are upset about Beyoncé's latest album—here's why

It turns out that, sometimes, even Beyoncé *can* do wrong. On June 28, the singer released the trailer for her upcoming visual album, Black Is King. Written, directed and executive produced by Queen Bey, the visual album—which is set to be released on Disney+ on July 31—is advertised as a companion to 2019’s live-action remake of The Lion King. ICYMI, Beyoncé not only voiced Nala in the film, but also recorded new music for and curated the companion album The Lion King: The Gift. According to a press release for Black Is King, the visual album “reimagines the lessons of The Lion King for today’s young kings and queens in search of their own crowns.” The release further notes that the film honours the “voyages of Black families” throughout time through “a tale about a young king’s transcendent journey through betrayal, love and self-identity,” and is an affirmation of a grand purpose, “with lush visuals that celebrate Black resilience and culture.”

Based on music from The Gift, Black Is King will reportedly feature some of the album’s collaborators and is referred to as “a celebratory memoir for the world on the Black experience.” In an Instagram post sharing the trailer, Beyoncé wrote about her “passion project,” saying while it was originally filmed as a companion piece to The Lion King: The Gift, “The events of 2020 have made the film’s vision and message even more relevant, as people across the world embark on a historic journey. We are all in search of safety and light. Many of us want change. I believe that when Black people tell our own stories, we can shift the axis of the world and tell our REAL history of generational wealth and richness of soul that are not told in our history books,” she continued. “With this visual album, I wanted to present elements of Black history and African tradition, with a modern twist and a universal message, and what it truly means to find your self-identity and build a legacy.”

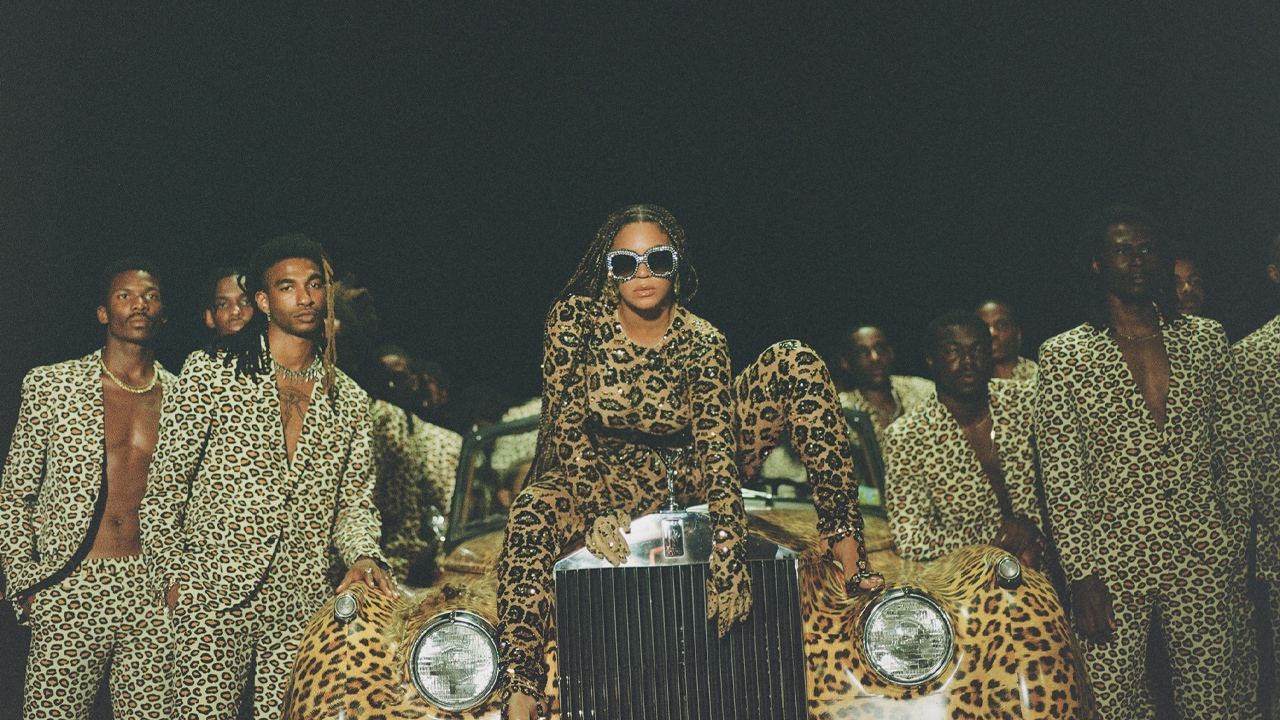

And—as with most things Bey produces—news of the visual album sent the internet into a freakin’ tailspin, with everyone and their mom hyperventilating over the impending release and gawking at the über gorgeous visuals in the trailer. While it’s just a glimpse, the trailer for Black Is King features Beyoncé, as well as a host of other Black creators and talent—many of whom are from Africa—decked out in traditional outfits, with biblical references and Beyoncé’s soothing vocals laid over top.

It looks amazing. But the album doesn’t feel amazing for everyone. Shortly after the trailer was released, several academics online started critiquing the new project; specifically, Beyoncé’s depiction and commodification of Blackness, and the homogenization and romanticization of Africa. These critiques can be difficult for the singer’s devoted fan base to contend with; after all, this *is* Beyoncé we’re talking about. But that doesn’t mean that they aren’t valid points—or that we shouldn’t listen to what people are saying.

There is more than one African culture

For Judicaelle Irakoze, an Afro-political feminist and academic based in Maine, the trailer for Beyoncé’s Black Is King reminded her of 2019’s The Gift in that both projects mainstream and amalgamate African culture. A lifelong Bey fan who still loves the performer—but is critical of her art as an academic—she says: “When I listened to the album, The Gift, my first critique was that Beyoncé mainstreamed South Africa and Nigeria.” According to Irakoze, with a recent surge in awareness about Nigeria and the Nigerian music industry, the two main countries that are often “known” outside of Africa tend to be South Africa and Nigeria. But there’s so much more to the continent that that. “In The Gift, Beyoncé worked with artists from South Africa and then carried it on and called it a gift to the African continent,” Irakoze says. “Which was wrong.” (The Gift included songs with Cameroonian artist Salatiel and Shatta Wale of Ghana, however it featured predominantly South African and Nigerian artists.)

Irakoze says the trailer for the album is “too much,” seemingly trying to amalgamate a plethora of different cultures and customs into a singular depiction of Africa—something she attributes to an effect of colonialism. “People think of Africa as one country,” Irakoze says. “But Africa is 54 countries and different ethnic groups, and these different ethnic groups have their own story [and] have their own ways of living. So Beyoncé talking of a whole continent as this one big family group, it doesn’t make sense.”

https://twitter.com/divanificent/status/1277198245589069824?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw%7Ctwcamp%5Etweetembed%7Ctwterm%5E1277212909068828673%7Ctwgr%5E&ref_url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.flare.com%2Fwp-admin%2Fpost.php%3Fpost%3D766402action%3Dedit

you can love beyonce and criticize the harm her art creates when it appropriate african cultures and glorifies them under black capitalism.

I love her so much and want my queen to use her power and status not to glorify africanness rooted in power game against the white gaze

— Judicaelle Irakoze (@Judicaelle_) June 28, 2020

Some argue the album romanticizes pre-colonial Africa

Irakoze also takes issue with the trailer because it taps into a side effect of colonialism, something she says “colonialism came and stole from us,” which is “the ability to evolve.” She explains that because colonialism was so obviously terrible and robbed so many people and countries of their history, cultures and lives, “we think what we were before colonialism was better.” This idealization, she says, is not necessarily accurate. “Africa before colonialism was not a heaven. Africa before colonialism was not a place where everybody was a king or queen,” she says, noting how this romanticization even found its way into the album title, Black Is King. “Africa before colonialism was full of African imperialism—kingdoms fighting each other, slavery within kingdoms, class oppression, women’s oppression—so what Beyoncé portrays to us is that narrative that, ‘Oh, we all were kings and queens.’ And that is a lie.” Irakoze points to well-known stories of women like Cleopatra and Queen Nefertiti—the Egyptian monarch who Beyoncé famously emulated on-stage during her Coachella performance—which are often used as examples of women thriving in a time when most were, in fact, oppressed.

“[These were] queens that we adore and idolize and romanticize, and we want to relate to them without realizing the context of where they come from,” Irakoze says. Often, these stories are used as an example to say that “before colonialism, African women were killing it; they were enough, [they were] super human beings.” But, as she points out: “Cleopatra was not a typical average African woman. And that is what Beyoncé did [with her performance]. Beyonce didn’t show us a typical average African woman. So what does it mean to say ‘Black is king?'” she asks. “No, not every Black person was a king, not every Black person had the potential to be a king.” This is especially important to remember considering the fact that—in the context of the African content—some ethnic groups are still living with generational pain and trauma that their ancestors endured during these monarchical times. “My grandfather was a slave in the kingdom before colonialism,” she says, so what is Black Is King?”

For Irakoze, this glorification and romanticization is problematic in a few ways, but most predominantly in the fact that it discourages progress, as people may look at the past through rose-coloured lenses, contributing their suffering solely to colonialism and failing to consider the other factors that may have impacted it. “It is problematic because it keeps us from imagining a better Africa,” Irakoze says. “We think what we were was better. So it keeps us from moving forward; it keeps us from seeing that what the African continent suffers today isn’t only because of colonialism.

honoring our ancestors isn't to create false illusions of what they were. being dishonest to ourselves, won't change the painful realities of what we inherit.

it's time to realize we deserve an africa way better than what it was before the whites steal from us.

— Judicaelle Irakoze (@Judicaelle_) June 28, 2020

“Women and girls were being oppressed before colonialism came,” she emphasizes. “But what colonialism did was to shape it to religion and different European ways of being—but they didn’t introduce it to us.”

And, not only that, but it plays into an antiquated vision of the African continent and people by Western countries. “[Beyoncé’s] contributing to that idea similar to ‘white saviour behaviour,'” she says. “Someone who’s not been on the African continent, and now they come and act as if they know what people in the African continent need.” Irakoze refers to a tweet she saw after the release of the trailer, in which one fan tweeted: “Do Black people in America actually know that Africans live our lives like them. Like we wake up and tweet like they do.”

https://twitter.com/Dimssoo/status/1277560187742814208

As someone who was born and raised in Burundi, Irakoze says she has seen this interaction—an effect of colonialism—firsthand. “I can understand how Black people in America behave towards the African continent. They lack that relationship with the continent, and then Africans realize that people want to interact with us as if we are some project.”

There’s also the question of cultural appropriation

It’s clear to some that—from the trailer at least—Beyoncé may have just not done her homework. A fact made all the more upsetting considering that she doesn’t necessarily have connections to the African continent (as several users online pointed out, Bey has never even done a tour in Africa). “Seeing someone who is not also part of [the African content], embody different cultures at once—it made us very uncomfortable,” Irakoze says of criticisms online. [“And the question may be], how is she appropriating when she’s Black? But the question isn’t that she’s Black, the question is that she may not have connection or roots to the African continent. And that is enough for her to not just bring different cultures together into a song without understanding the context of it.”

Beyonce needs to stop using Africa as a trope because she won’t even come here to tour. https://t.co/hScoZC6vrh

— Nirvana ♡︎ (@noxytea) June 28, 2020

But is it even possible for an artist without roots to the continent in question to authentically tap into the culture and represent it in a respectful and non-commoditized way? For Irakoze, the answer is yes—especially when it comes to Beyoncé, because fans have already seen her tap in to Black pain and experience, and deliver something authentic in the form of 2016’s Lemonade and her April 2018 Coachella performance. “I think the way she has been very careful in creating music when it comes to Black oppression in the States, she can do that when it comes to the African continent,” Irakoze says. “Because if you look at her music, her song “Freedom,” or you see how careful she was when she did Coachella; how carefully she studied [history] to make sure she doesn’t cross a line. And why did we love Coachella? Because even though she used Black pain, she used it very carefully because she can relate to it. She’s a part of it. So now she can authentically sell it.”

And critics are just asking for the same care with her latest visual album, and the cultures and experiences it’s tapping into. “We want her to do the work,” Irakoze says. “Find African people on the continent or outside of the continent who understand this, sit with them, ask for guidance…She can hire us and we can find a way to connect what it means to decolonize Pan-Africanism in her art, and that will sell. Of course it will be stealing our revolution, but it will make sense.” (Psst, Beyoncé…Irakoze is available!)

But it’s still important to give the album a chance

It’s important to note, of course, that these critiques are based off of a trailer, and the full album may include a wider array of depictions of Blackness. (In fact, Irakoze says: “I can’t wait to watch the film and maybe, hope to prove myself wrong.”) And since the trailer was released, several people have shared their involvement with the production in various countries across Africa.

#BlackIsKing ~ I was tapped to contribute and direct the Ghana 🇬🇭 portion of the film there was nothing like contributing to this vision through narratives on the ground in my home country. This wouldn't be possible without my on the ground Ghana team! pic.twitter.com/w6lm2lZSQu

— Joshua Kissi (@JoshuaKissi) June 29, 2020

For Sisa Zekani, an entertainment and culture critic in Port Elizabeth, South Africa, there’s a lot to celebrate about this new project. “My first thought was ‘finally,'” he says of watching the trailer. “I didn’t expect it to be so affirming.” While Zekani says he understands where much of the critiques are coming from—particularly surrounding the idea of Black celebrities monetizing Blackness—in a way, that’s what art does.

“I think art is supposed to reflect your experience or at least the experience of those around you,” he says, “[and] her art can’t come from anywhere but the Black experience. And while some online have pointed out the fact that Beyoncé is potentially pulling from a Black experience that’s not entirely rooted in her own, Zekani doesn’t necessarily agree with this take. “I’m someone who believes African Americans should have access to Africa because of ancestral ties; this is something that was taken from them and if they want to learn more, contribute and participate in the cultures they identify with, they should be given the space,” he says.

Zekani points to some of the announced collaborators on the album, like Busiswa, Burna Boy and Shatta Wale (who represent South Africa, Nigeria and Ghana), as examples of Beyoncé not trying to speak for or amalgamate the continent as one. “Beyoncé isn’t trying to speak for Africans,” he says. “We know that the voices that are featured on the project will largely be African musicians, African directors, African stylists and African researchers. I trust Busiswa to know more about the Xhosa experience than anyone else, and I think Beyoncé knows that, which is why she’s on the project.”

https://twitter.com/Titanbaddie/status/1277889054730792960

Ultimately, he says, critiquing art that hasn’t been released yet is premature, “and I’m more interested in discussing how this will affect the landscape for African artists going forward.” Because it’s a landscape—like Irakoze noted—that has long been overlooked. “African art has been largely left on the outside of mainstream entertainment. There are representations of us [like The Lion King and Black Panther] that have been unsuccessful in changing the situations and realities of the African artists they’re inspired by,” he says. “Beyoncé is funding a project that showcases and puts at the forefront the culture, art, words and voices of African artists.”

“We deserve our K-pop moment. African art has been a reference point for so many generations but we’ve never been at the table, so for this kind of project to be coming out is of value and should be celebrated and deserves to be seen. Africa deserves to eat—why wait?”

One thing’s for sure: We’ll all be watching.