The T-shirt Revolution: How a Wardrobe Basic Became a Sign of Protest

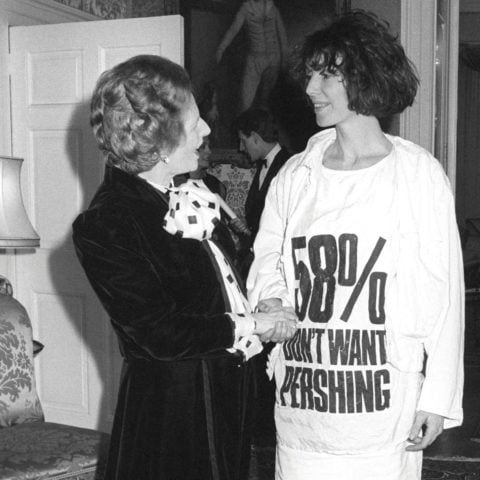

Decades since Katharine Hamnett met then prime minister Margaret Thatcher wearing a T-shirt that denounced missile deployment in West Germany, we’re back to wearing our political activism on our sleeve.

T-shirts have always been political. Even 100 years ago, when they were marketed as undergarments, they were part of the U.S. military uniform during the First World War. During the 1950s, wearing them as outerwear or under a leather jacket, à la Marlon Brando or James Dean, became a subversive act.

But to participate in the T-shirt revolution, you’d have to have been around in postwar London, when the democratization of education produced the irreverent art-school student alongside the rising popularity of silkscreen printing. “Silkscreening exploded in the 1960s,” says Dennis Nothdruft, head of exhibitions at London’s Fashion and Textile Museum. “It’s a basic process you can do at your kitchen table, and it became a mainstream medium for expression.”

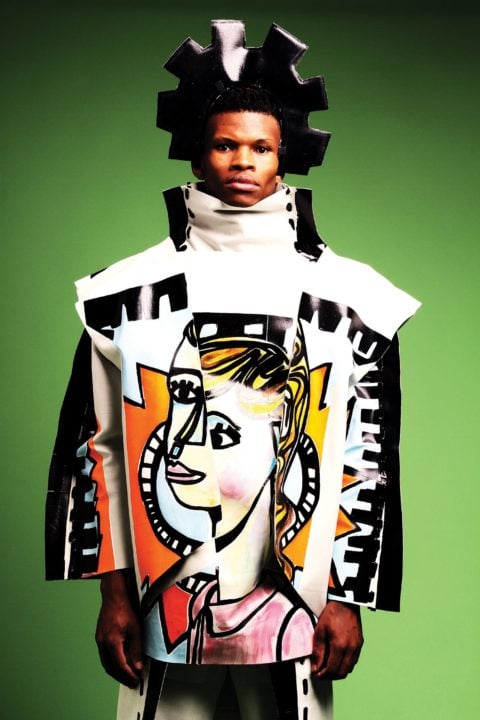

On February 9, Nothdruft launches his latest exhibition, T-Shirt: Cult | Culture | Subversion, featuring roughly 200 sartorial artifacts from the worlds of fashion, music and politics and the intersection of the three. It maps the T-shirt’s trajectory from nondescript throwaway to marker of identity, with rock music as a catalyst. The Who, the Sex Pistols and David Bowie make appearances in a gallery titled “With the Band,” which contemplates T-shirts as objects worthy of collection by teens and other rebels rejecting the status quo. “They were billboards aligning you with a group of people saying ‘This is who I am,’” says Nothdruft.

Designer Vivienne Westwood dressed that cohort from her London boutique, Seditionaries, tugging and tearing the classic T-shirt shape to create tension. Just over 15 years later, Martin Margiela took a less political stance, deconstructing silhouettes and moving necklines.

Between them came Katharine Hamnett, with her slogan tees for bands like Frankie Goes to Hollywood. Text T-shirts have gone in and out of style, but what makes this exhibit timely is that, decades since Hamnett met then prime minister Margaret Thatcher wearing a T-shirt that denounced missile deployment in West Germany, we’re back to wearing our political activism on our sleeve.

London label House of Holland’s Henry Holland, who once put out T-shirts teasing fashion designers with slogans like “Cause Me Pain Hedi Slimane” and “Get Yer Freak On Giles Deacon,” has donated two designs from his recent Brita collaboration that scream “Don’t be a waster” and “Single use plastic is never fantastic.”

More than 25 years since Keith Haring’s “Ignorance=Fear, Silence=Death” AIDS awareness T-shirts, Nothdruft is rifling through a new crop of LGBTQ shirts. “Yes, we’re still having these stupid conversations,” he says. That’s not to say T-shirts have become any less angry or rock ’n’ roll. “It’s what you’re saying with the T-shirt that makes it rock ’n’ roll,” says Nothdruft. “There’s always the potential to annoy people with what you’re wearing on your chest.”