Will Fashion Automation Mark the End of Seamstresses and Retail?

"I wanted to remove myself from the fast-fashion cycle where every idea that you have, that you produce, that you make expires in four months or six months and is not valuable at all anymore."

If you were to close your eyes and imagine the clothing of the future, you’d likely picture severe, angular cuts in synthetic fabrics, like something out of Blade Runner. Set in 2019, Ridley Scott’s ’80s version of the future still seems very far away. In all likelihood, it was Spike Jonze who got it right with his 2013 movie Her. One of the most-talked-about aspects of the film was the high-waisted pants, worn by Joaquin Pheonix, that were at odds with the high-tech world in which they roamed. “Spike liked to describe them as your pants giving you a hug around your waist,” costume designer Casey Storm told The New York Times. “It’s an emotion that felt nice to us.”

This sartorial sentiment is echoed by Ministry of Supply’s Boston-based chief design officer Gihan Amarasiriwardena when he talks about fashion automation and his brand’s 3-D blazer, a seamless garment that is made by a machine in 90 minutes to a customer’s exact specifications for $450. Customers say it feels like “wearing a hug,” says Amarasiriwardena, adding that consumers can now become more invested in what they’re wearing and how it’s made. “It allows us to build a deeper relationship with our products rather than just something that you buy and then throw away.” An MIT-trained chemical engineer, Amarasiriwardena was lured into the apparel business by the prospect of bringing professional workwear into the future. “All of this performance existed in the outdoor space and the athletic space, but so little of that has translated into what we wear every day,” he says.

Mass fashion has chased cheap labour around the world, moving factories from North America to Asia, and now parts of Africa, instead of trying to find new, efficient and ethical ways to innovate production.

Unlike other industries that have embraced technical manufacturing processes, mass fashion has chased cheap labour around the world, moving factories from North America to Asia, and now parts of Africa, instead of trying to find new, efficient and ethical ways to innovate production. Because of its trendsetting nature, fashion typically focuses its energy on seasonal stylistic changes rather than functional innovation. But the rise of fashion automation and digital production is finally trickling into the fashion world.

Last year, Jonathan Zornow created Sewbo, a process that chemically stiffens fabrics to allow automated sewing robots to produce an entire garment. A software engineer, Seattle-based Zornow was inspired by an episode of How It’s Made on jeans. “It seemed strange that we wouldn’t have more automation in that field; I had assumed that robots were making all of our clothes,” he told Fast Company. With his new process of fashion automation, this assumption may come to fruition. A 2016 study by The Brookfield Institute for Innovation and Entrepreneurship found that 42 per cent of the Canadian labour force is at high risk of being affected by automation over the next decade or two.

One component of fashion automation is 3-D printing. Typically thought of as architectural objets, clothing produced by 3-D printers first made waves in 2010, when Dutch designer Iris van Herpen sent her award-winning couture down the runway at Amsterdam Fashion Week. Impressive feats of imagination they may be, but wearable they are not. Today, these otherworldly creations are being brought down to earth by Canadian labels like Sid Neigum, who in June won a $50,000 grant to explore 3-D printing. Even he was surprised by the soft, flowing fabrics created by the technology.

“It’s not what you imagine when you think of 3-D-printed garments, but I think that this is a really interesting way to pursue what we’re doing,” he says. Neigum follows Daniel Christian Tang, a jewellery house run by two architects and an engineer who print gold and silver baubles from powder. Designer and co-founder Mario Christian Lavorato predicts that digital fashion automation is poised to take over. “Right now, 3-D printing is still kind of this new industry that’s finding its way in medical and other industries but not really in retail and mass production,” he says. “Given the speed of this industry, it will become ridiculous. It’s eventually going to become the only way to produce products.”

It’s a process that’s currently being adopted by notorious digital disrupter Amazon. In April, the e-commerce giant was awarded the patent for an on-demand computerized system of made-to-order clothing that includes textile printers, cutters and an assembly line. With Amazon’s clout in the online shopping sphere, it’s only a matter of time before we’re all clicking to buy our very own digitally printed wardrobes.

The benefits of digitally produced, made-to-order clothing are multiple. Up to 30 per cent of fabric is typically discarded during the standard manufacturing process, but this is virtually eliminated with digital production; it also means the elimination of overstock supply, since consumer-based ordering guarantees a buyer for every item produced. Fashion automation also reduces the amount of physical manipulation required in the process. “The best part is, because it’s technology and you’re not really relying on a human, the amount of human error is almost zero,” says Lavorato. While there may be only one person operating the machine—instead of many low-paid staff involved in high-volume cut and sew lines—he or she is a highly trained technician, creating garments in computer-aided design (CAD) and printing them live.

As shoppers, we’re already beginning to move away from rabid fast fashion consumption. In March, Zara reported that profitability had shrunk to an eight-year low. Anyone who has bought a $10 T-shirt on a whim can attest that fast fashion is not engineered for longevity—physically or emotionally. Being invested in the creation of a garment that was made just for you brings feelings of attachment, which means you’ll want to wear it longer, while its technical or tailored production means that it will last longer.

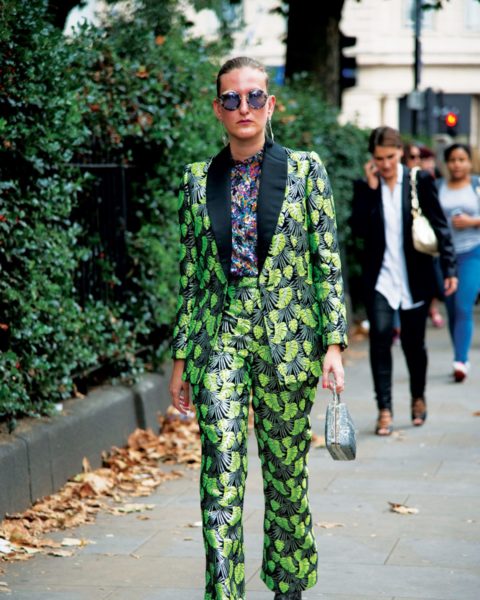

For the consumer, ordering custom-made clothing, whether a machine or a human creates it, means a renewed involvement in the creative process. “People are craving something that’s for them as opposed to just this illusion of choice,” says designer Philip Sparks, who runs his namesake label out of a studio in Toronto’s Junction neighbourhood. After creating seasonal collections for eight years, Sparks transitioned to a new kind of design with custom tailoring in 2015. “I wanted to remove myself from the fast-fashion cycle where every idea that you have, that you produce, that you make expires in four months or six months and is not valuable at all anymore as opposed to making something that somebody wears and keeps and takes care of,” he says. His one-of-a-kind pieces, mainly suiting and outerwear with price points lower than the big designer brands, take eight to 10 weeks to complete. There are multiple fittings along the way, and the end result is nearly always an evolution from the initial concept. His clients are extremely involved in the creative process, which is more open-ended than working with a digital machine where you select from a series of options rather than come up with the idea yourself.

A seamless garment made by a high-tech machine may feel like wearing a hug, but it can’t replace the love that goes into making something by hand. “I get to make people feel really good about themselves,” says Sparks. “It’s amazing. It makes me feel like I’m doing something that matters. I think you’re getting more out of the experience with another person than you are when you watch a machine do it.”