The Father of Basara, Kansai Yamamoto, on his Louis Vuitton Collab

Just like glam rock’s lurid sequined looks offered a release from the high unemployment rates in the 1970s, today’s basara aesthetic may be a distraction from the political dumpster fire of 2017.

Google “basara” and you’ll mostly find results for a ’90s manga book about a 15-year-old girl seeking revenge against an evil king set in post-apocalyptic Japan or for hotel bookings for a remote village in Serbia. But dig deeper and you’ll find that basara is also a Japanese term encompassing a luxurious kookiness that is basically the sartorial definition of “extra.”

Characterized by colourful attention-grabbing garments, it exists in stark opposition to the concept of “wabi-sabi,” the quiet simplicity and Marie Kondo-esque minimalism that has become de rigueur over the past decade. Basara, which roughly translates as “to dress freely,” presents a joyful, exuberant vision that clashes with the intellectual rigour of designers like Issey Miyake, Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo, whose sometimes-abstract designs have been synonymous with “Japanese fashion” since the 1980s.

Basara is the brainchild of a different Yamamoto: Kansai, who showed in London a decade before his Japanese contemporaries to produce designs so vivid and splashy that they almost defy comprehension. When I speak to him over the phone from his hotel in New York, Kansai suggests that wabi-sabi has achieved cultural saturation because it’s easier for North Americans to understand.

“Western people don’t have wabi-sabi feelings,” he says plainly. In other words, the humility and austerity of wabi-sabi has been embraced as trendy particularly because it remains foreign. A sense of busyness and overstimulation is already so familiar to our culture that at first glance it doesn’t seem to merit its own word. But basara is more—it’s about flaunting assertiveness and individuality using a palette of kaleidoscopic colours. As Kansai says, “Basara is in my DNA.”

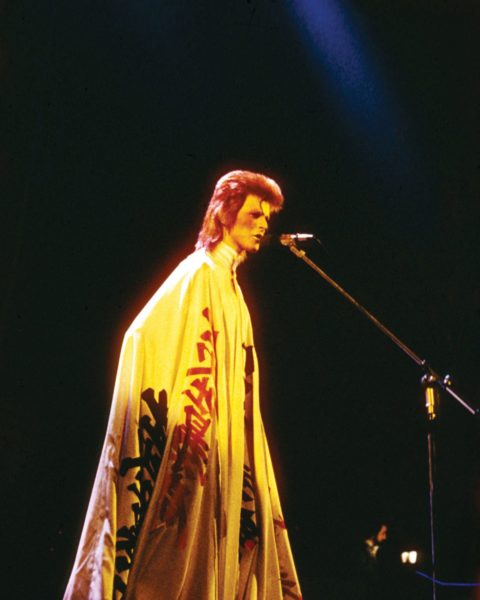

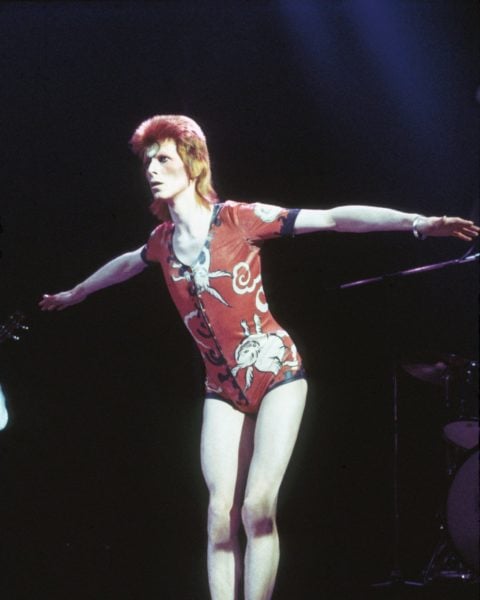

When Kansai brought his first collection to show in London in 1971, “English people were very shocked,” he recalls. “They didn’t have any imagination about Japanese [culture].” Kansai quickly found a collaborator in David Bowie: He designed the performer’s Ziggy Stardust and Aladdin Sane costumes.

“David Bowie was the first person to think of a rock concert as a theatrical production,” says Philip Auslander, a professor at Atlanta’s Georgia Tech and the author of Performing Glam Rock: Gender and Theatricality in Popular Music. Kansai’s designs were closer to sculptures than plain old garments, which ensured that every fan—even the ones forgoing platform boots—could watch Bowie perform from the back of the concert hall. “[Bowie’s] concept and my concept were very similar; that’s why we worked together,” says Kansai. “Both of us were very aggressive about new creations. David Bowie was basara in a Western way, and I am the Japanese way.”

For Louis Vuitton’s Resort 2018 collection, artistic director Nicolas Ghesquière enlisted the 73-year-old designer to create some of the collection’s bold prints, including the recurring kabuki-mask motif seen on dresses and bags. The entire collection pays flamboyant homage to Kansai, featuring plenty of loud leopard print, gilded sequins (a nod to Japanese Noh theatre), sleeves buoyant enough to resemble one of Bowie’s stage costumes and kumadori-inspired makeup.

We can also see Kansai’s influence in Alessandro Michele’s moth-eaten disco designs for Gucci, where the proliferation of embroidery mixed with logo print reads like an adolescent playing dress-up in her grandma’s closet before heading to a glam rock concert. At Balenciaga Spring 2018, Demna Gvasalia showed trousers that incorporated houndstooth print and plaid paired with a lime green ruffled shirt and red spiked heels. At Sacai, the high-class-harlequin look reigned supreme, as if an entire thrift store had been ransacked and then repurposed into a single outfit. Even Céline’s Phoebe Philo, known for spearheading the new minimalism when she joined the house in 2009, embraced basara for Spring 2018 with a collection that was full of bright colours and kooky details like off-the-shoulder capes and two-sizes-too-big floral-patterned polo shirts.

“My work is not so easy to recognize or to make a new creation, but they did it,” Kansai says of the Louis Vuitton collaboration. For the past two decades, Kansai has distanced himself from the fashion industry, citing a lack of inspiration as the reason for his absence. But watching Louis Vuitton nail the essence of basara in its Resort 2018 collection has inspired Kansai to stage a comeback. “I have 20 years more to be a fashion designer,” he says. “Louis Vuitton cannot make all my collections. I have to make one by myself.” Kansai is currently working on designs for a fashion line under his own name, slated to launch at his fashion show next June in Tokyo.

It’s easy to suggest that basara’s current moment is due to a desire for escapism. Just like glam rock’s lurid sequined looks offered a release from the high unemployment rates, power cuts and IRA bombings of Britain in the 1970s, today’s everything-but-the-kitchen-sink aesthetic may well be a distraction from the political dumpster fire of 2017. After all, “there’s plenty to want to escape from,” says Auslander. Neo-Nazis are a threat to public safety, powerful men are commonly outed as prolific sexual abusers and the world inches closer to nuclear war every time Donald Trump hits the “send tweet” button.

Yet critics suggest that in 2017, fashion has reached a stumbling point where the only thing holding it together is its own utter lack of consistency. Perhaps it’s the lack of unifying trends, rather than a need to escape, that speaks to the true essence of basara. For some, the concept of dressing freely might be visually confusing, but for others, it might be “spontaneous.”

The ’70s glam rock styles that current designers are taking their cues from contain tinges of what is known as the “carnivalesque,” notes Alison Blair, a PhD candidate at the University of Otago in New Zealand. Historically, carnivals existed as a way for people to escape mundane reality; they put on costumes, and that provided a temporary reprieve from the every day. Blair suggests that the carnivalesque becomes particularly important during times of crisis and change because revelling in carnivals makes the periods of austerity that follow easier to bear.

Trump’s presidency has infused a new sense of immediacy into the cultural vocabulary—a sense of urgency that comes from not knowing what comes next. However, Kansai remains unfazed. “The world is always changing and continues to change,” he says. “We have to look forward.” Basara contains many more facets that Kansai has yet to explore: “I have to continue. I have to go deeper.”