Is Genderless Makeup the Beauty Industry’s Final Frontier?

It’s no secret that beauty has always been fashion’s friendlier, more approachable sister. It’s inclusive of people of all shapes and sizes, and it casts an even wider net when it comes to socio-economic status. If you can’t afford a designer bag, a designer lipstick allows you access to the brand at a fraction of the price.

However, issues of race and age remain. And while there is still a ways to go, strides have certainly been made when it comes to inclusivity. Today, many brands offer a wide range of shades that cater to different skin tones. Ensuring a diverse age representation has been a slower process, but when Charlotte Rampling and Susan Sarandon landed campaigns for Nars and L’Oréal Paris, respectively, at age 69, it became clear the tide was beginning to turn.

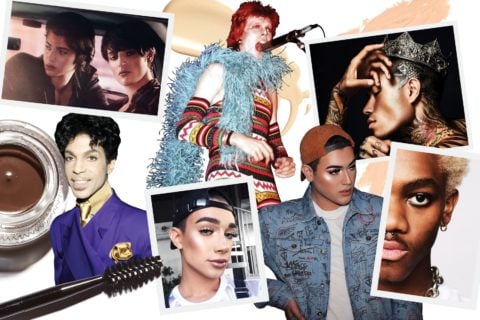

That brings us to gender, the beauty industry’s latest boundary. While men have worn makeup as far back as ancient Egypt, it was celebrities like Boy George, Prince and David Bowie who began the male beauty movement in the ’70s and ’80s. “They were so over-the-top,” says Karen Grant, global beauty industry analyst at market research firm The NPD Group. “They were these super-stylized individuals who were so legendary and famous and out of reach.”

But the needle started to move in the direction of mortals in the fall of 2015, when M.A.C (which has always said it is for all ages, races and sexes) collaborated with model Stephanie Seymour’s sons, Harry and Peter Brant, on a collection of gender-neutral products. The brothers, who have been wearing makeup since high school, launched a second collab with M.A.C—which included brow gels, lip stains and eyeshadows—last summer. And within the past year, major brands have signed leading “boy beauty” social media influencers as their ambassadors: Maybelline New York tapped Manny Gutierrez, CoverGirl enlisted James Charles and Rimmel London employed Lewys Ball. But, to be clear, this isn’t drag. They identify as male—they simply enjoy doing, and wearing, makeup.

“The younger male is very open to looking better,” says Grant. “There is less resistance to things that can enhance a man’s look.”

And whether it’s the vloggers mentioned above, who are known for wearing a full face of makeup—glitter cut creases, sharp contour and enough highlighter to light up a small village—or Hollywood actors, who rely on concealer, bronzer and brow gel to get through a red carpet appearance, men exist on a spectrum in terms of how much they’ll wear. Men are not only wearing makeup but also using the same products as women.

The beauty industry’s response to this has been swift. There’s a move toward a unisex, or genderless, approach to makeup, which WWD insists is due to “Generation Z’s disinterest in gender identification.” Grant agrees. “This generation is so not thinking ‘You can’t do that,’” she says. “If you tell them they can’t do something, they’ll want to do it.” But it’s not just millennial brands like Milk Makeup and Anastasia Beverly Hills, both of which feature men and women in their campaigns, that are taking a gender-neutral approach. Charlotte Tilbury, the makeup artist and the brand, is known for being hyper-feminine, yet it’s clear that her new Unisex Healthy Glow moisturizer caters to both men and women. “If the market [for unisex products] were bigger, I would have done it earlier,” she says, adding that she noticed that men were starting to buy her skincare products, like Charlotte’s Magic Cream and Wonderglow. “Men are just as tired, hungover, whatever, as women. Yet as women, we can wake up and paint the health back into our faces. I find it unfair that men never had that.”

Celebrity groomer Kumi Craig, who has worked with Hollywood’s biggest names (like Justin Bieber, Drake and James Franco) for 18 years, has noticed a change in her clients’ attitudes. “I remember when guys didn’t even use moisturizer,” says Craig, who uses bronzer, concealer and a translucent powder on all of her clients. “Now they’re very involved.” She attributes much of the shift to HD cameras and the instantaneous nature of social media. “You can really see the lack of sleep and flying on airplanes on their faces. I was working with a client, who was about 65, who said: ‘Back in the day, we’d do all of this without anything on. Now I get my makeup done for a radio interview.’”

Grant acknowledges that cameras play no small role in these evolving attitudes. “We’re living in a selfie-driven world,” she says. “Guys want to look great [in photos]. Younger males have been introduced to grooming from an early age, so the constructs and stigma aren’t there.” Macho culture is certainly not as prominent as it once was, and cultural differences may play a role in that shift.

When K-beauty exploded in popularity a couple of years ago (think BB creams, double-cleansing and cushion compacts), it brought with it more than just innovative products for women; it introduced us to Asian ideals of male beauty. “Western culture has always positioned different cultures as ‘other,’” says Ingrid Mida, fashion research collection coordinator at Ryerson University in Toronto. “The dominance of a certain kind of masculinity in Western culture plays into that. Whereas in South Korea, it’s very common for men to spend a lot of money on their skin. Now these [gender] binaries are falling away.”

Craig adds that many of the male celebrities she works with pick up on the importance of beauty and grooming when they’re in the East. “They go to China or Korea to promote films, and they really notice that men there are grooming their eyebrows, getting facials and wearing foundation and makeup.”

Grant predicts that the beauty industry in North America will adopt a similar attitude, viewing makeup as an extension of grooming, but it won’t be on the same scale. “There are trendsetters who are making it more acceptable for men to venture into this space, but I don’t think makeup is ever going to be something that works for the majority of males,” she says. As for the future of makeup, Grant believes the terminology will simply change over time. “I think we won’t call it ‘makeup’ anymore. It’ll be gender-blurred, like the term ‘hair gel’ is. If a guy uses hair gel, we don’t think ‘Oh, that’s a girl product.’ We just think of it as hair gel.”