A Longtime Feminist Activist Speaks to Where the Women’s Movement is at in 2018

"I believe that in 30 years from now, we will be looking back in the history books — or on the history iPads, or whatever those look like — and we will be saying: 'this was the moment in time that things shifted.'"

Jess Tomlin has been working in women’s organizations for fifteen years. As the CEO and president of The MATCH International Women’s Fund, Tomlin is the kind of feminist who can toss memorized statistics on forced marriage and domestic violence casually into a conversation. In Tomlin’s own words, she “lives, eats and breathes women’s issues.”

And yet, when her 8-year-old daughter came to her to complain about a boy at school who bugs her — pulling her hair and pushing her up the stairs — Tomlin said: “He probably likes you.”

Tomlin quickly realized that she was falling back on a deeply held sexist assumption — one that she’d been spoon fed from birth — and that it’s not okay for a boy to show you he likes you by hurting you, whether you’re 6-years-old or 60-years-old. “I realized in that moment how deeply entrenched and deeply rooted some of those traditions, narrative, stories, assumptions and attitudes are,” she says, “because they even exist within me.”

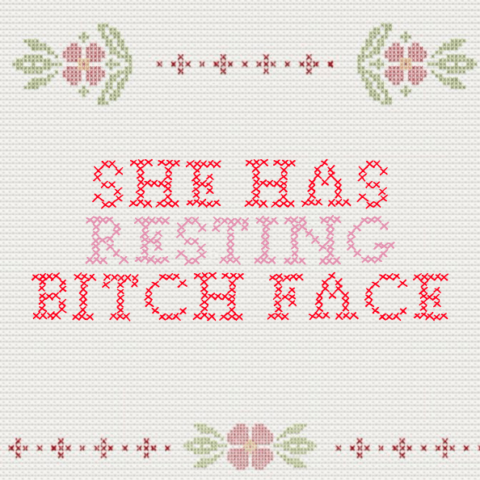

The women’s right movement is at a tipping point, with women from all walks of life sharing their experiences of being mistreated, abused and objectified. But much of marginalization is rooted in our words: it’s hiding in plain sight in the cultural language that continues to be used every day. Like your great grandma’s cross-stitch, these phrases are passed down from one generation to the next — and often times by women.

In anticipation of International Women’s Day, and MATCH International Women’s Fund’s “Resting Stitch Face” campaign, I spoke with Tomlin about the power of the women’s movement in 2018, and what we need to do to keep it alive.

Will we look back at 2018 as the year the women’s movement hit its peak? Or can you see the momentum growing from here?

I truly believe that this is our sixties moment. I believe that in 30 years from now, we will be looking back in the history books — or on the history iPads, or whatever those look like — and we will be saying: “this was the moment in time that things shifted.”

The thing is, we don’t know what a totally equal future looks like. There is a whole deeper level of assumptions, bias, accepted truths, norms, attitudes and behaviours that are deeply rooted in all of us. Those things are messy, and those are the things that have to be resolved. And those things don’t get resolved in a march — it’s the deeper work. I don’t know what 10 years from now looks like, but I know it doesn’t look like this.

“Resting Stitch Face” reminds me of that embroidery photo that went viral in the early days of #MeToo. Do you think that sharing these little images on social media can actually change something? Or is this token slacktivism?

Particularly in Canada, I don’t see a lot of translation into action. And it’s mostly from the perspective of where people put their money. It’s one thing to demand change and grab a coffee to go be part of a march, and it’s another to say we need to be strategic about where we’re putting our money. Canadians have a perception that we’re global citizens, but the fact is when you look at charitable giving in this country eight percent goes outside of Canada. And of that, five percent goes to humanitarian or emergency funds. That means the long terms stuff, the stuff we’re talking about right now, gets about two to three perfect of Canadian charitable giving — and you can only imagine what’s actually getting to women and girls. So for me it’s less about slacktivism, and more about putting our money where our mouths are.

Are there any other problems you detect in the women’s movement? Whether it’s with #MeToo, Time’s Up or the movement as a whole?

The spokespeople for this movement are still, by and large, white women of privilege —and yet they’re the least marginalized. We’ve gotten to this place because of the intersectionality; because of how movements are coming together. When people don’t see themselves within these movements, they won’t participate. That’s when you lose the power, and you lose the real transformative opportunity.

What do you think is the biggest problem facing women today? Is there one thing you can pinpoint, or is there just too much?

I don’t know . . . the patriarchy? It’s the structural inequality that plays out in women’s lives, on women’s bodies, day in and day out. It’s about the laws that govern us and hold women back, it’s about how many children she should and shouldn’t have, how she’s represented in the workplace, whether she even has accessibility to the workplace, how much she’s paid when she gets there. This is why it feels really big — it is big.