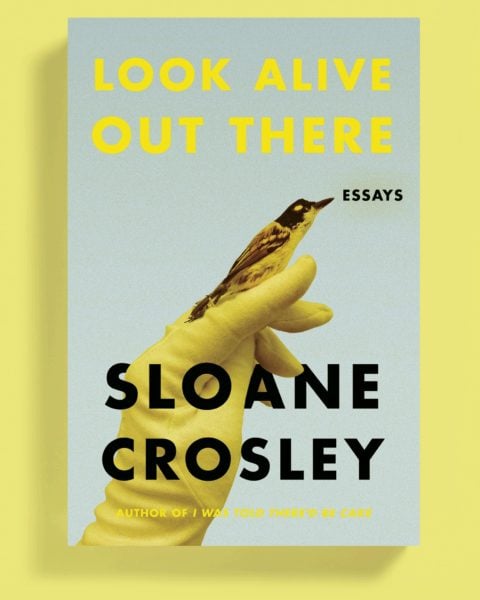

Sloane Crosley on Writing in a Post-Trump World, Books by Social Media Stars and Look Alive Out There

Like the best comedians and therapists, Manhattan-based writer Sloane Crosley possesses the uncanny ability to perfectly articulate your deepest thoughts and ideas better than you ever could. It’s like she coils herself into your brain, extracts some random, indescribable feeling and then spits it out fully formed on paper.

To wit: In her latest collection of non-fiction essays, Look Alive Out There, she describes the time-honoured tradition of going down the rabbit hole of WebMD (“a Choose Your Own Adventure Book in which all roads lead to death”) or the phenomenon of asking for travel tips for an upcoming vacation via a Facebook status “where comment after comment would compete in an e-thumb war for supreme regional wisdom.” She writes about that impossibly beautiful, kind-hearted friend everyone has—the one who wears jeans “meant for people with stilts for legs”—who would be infuriating except she truly believes that all of her girlfriends are as magnetically stunning as she is. It’s one of those books that by the time you’re finished reading it, pages upon pages are dog-eared and sentences underlined. You will feel seen.

Crosley’s breakthrough collection of personal essays, I Was Told There’d Be Cake, came out in 2008. Since then, she has written another New York Times-bestselling book of personal essays, How Did You Get This Number?, published her first novel, The Clasp, and guest-starred as herself on an episode of Gossip Girl. (OK, sure, she was the backup choice after another more famous author declined the part, but she happily took the gig anyway.)

In Look Alive Out There, Crosley bares all once again in essays that are at once funny, cringe-inducing and heartfelt, whether she’s dealing with noisy neighbours, interviewing her septuagenarian former-porn-star uncle or describing in intimate detail the travails of freezing her eggs. Inspired by great essayists before her, like David Sedaris, Joan Didion and Nora Ephron, Crosley isn’t afraid to reveal her own neurotic, emotional or vulnerable life experiences in the name of a good story.

I Was Told There’d Be Cake came out exactly 10 years ago. How have you noticed the personal essay as an art form evolve since then?

“The landscape for personal essays, specifically comedy written by women, has changed a lot. Without sounding too grandiose about it, I didn’t have a lot of company when I first published I Was Told There’d Be Cake. Now I do, and it’s great. It’s important for women to tell their stories.

“But I do think that there’s a tendency to think that it is easy. A good tweet doesn’t necessarily translate into a great essay. I think the tradition of the essay is getting lost in the shuffle.”

It’s interesting you mention Twitter because there are so many people with popular Twitter or Tumblr accounts who get a book deal, but the book turns out to be terrible.

“I don’t think it’s actually Twitter’s fault that this happens. The pithy one-liner, which is a lot older than Twitter, is an art form. Twitter is addictive and has a self-aggrandizing nature, but there are people who are really funny and they tell tiny stories in five words that still have layers. I think it’s strange that a publisher would look at that and think ‘That must be the tip of the iceberg.’ You wouldn’t look at a poet and think ‘Well, you must have a novel in you.’”

Why did you want to write The Clasp—a fiction? “A fiction.” “A fiction”…I don’t know why I phrased it like that.

“The way you said it, it sounds like I wove a string of lies. Part of the reason is I needed some new rules. If you have a nice painting you bought for your house, the first thing people will tell you is to move it every couple of years from one wall to another so you can see it again. I think that’s the closest analogy to why I go between fiction and non-fiction. With non-fiction, a good percentage of what you’re writing is not up to you—it’s the events in the world, in your life and in other people’s lives. That can be constraining. And then you move over to fiction and think ‘Thank goodness! I get to make everything up!’ and you realize it’s a whole different kind of work—every decision is yours, and there’s no such thing as ‘I don’t remember what happened; I was nine.’ All of a sudden, you sort of long for the days when you had the crutch of reality.

“When you write non-fiction, you have this constant decision of how much you react to what’s going on in the world. I handed in Look Alive Out There the day before Hillary Clinton lost. We still lived in a world coloured by Trump, but the world hadn’t changed completely yet. I edited the essays afterwards, and it was like there was an elephant in the room. I decided that everything doesn’t need to revolve around this unpleasant centre.”

I think the reader would be able to sense it if you threw in an essay last-minute that reflects a post-Trump world. It’s kind of refreshing not to read about him.

“I hope that’s the case. I think it’s important to remember that he is not our entire reality. It’s humanizing to get mad when a woman in a wheelchair robs you of your cab [which the first essay, ‘Wheels Up,’ is about] and to focus on that for a second. [We’re] so angry about the current political climate, we can forget the little [things] that give texture to the rest of our lives.”

I read in an interview from a few years ago that you tend to clear stories with the people you write about before publishing. Is that still the case?

“Basically, as long as they’re identifiable or they’re still in my life. I don’t run much by my parents because it doesn’t seem necessary. This isn’t Running With Scissors—I’m not outing them as horrible people. I’ve had some issues in the past—I eventually got disinvited to a wedding technically because of an essay. My personality is not to hurt people, but at the same time the other half of me has the same viciousness that any other writer has, which is ‘Everything is copy,’ as the great Nora Ephron once said. Luckily it hasn’t been a huge problem for me, except for that wedding.”

In the final essay in the book, “The Doctor Is a Woman,” you write about the experience of freezing your eggs. It felt more vulnerable.

“I call it the ‘blood on the field’ essay. When you’re writing essays, it’s not a giant narrative piece. The sense that you’re writing a whole book doesn’t really congeal until later, and when it does, it feels like ‘Now is my chance to tie in everything I feel is personal to me and relevant to the audience.’ I have an aversion to diary-like essays, so perhaps I feel like you have to earn that kind of story. If you’re reading the essays in order, you get to really know me. It makes it more impactful to put that essay at the end and leave on a heartfelt note, not just a funny note.”

Do you ever get readers who, after reading your essays, think they really know you and want to be your best friend?

“I do get that. What’s weird is that we probably would be. All of the people who come to my readings—they’re way more than I deserve. They’re smarter, they’re better dressed, they smell nice. But it’s just that I’m in and out of town so we’re probably not going to be best friends. I’m always really flattered by it, frankly.”