Lisa Moore Reminds Us That October Isn’t All About Halloween

Every month has a mood, a feeling, some combination of memories, moments and nostalgia. You know it—you feel it—even if you’ve never really thought about it. To help encapsulate the moods of the months, we’re asking novelists to take on the calendar and evoke the feelings of each season through fiction, memoir or prose. Here, author of Something for Everyone and February, Lisa Moore, illustrates another month: October. See how other authors have represented your favourite months here.

I don’t know how I fell asleep, but I remember how I woke up. A black shape rose up in the radiance behind my eyelids. One of the horses had found me and was rising up on its hind legs. It would step on me.

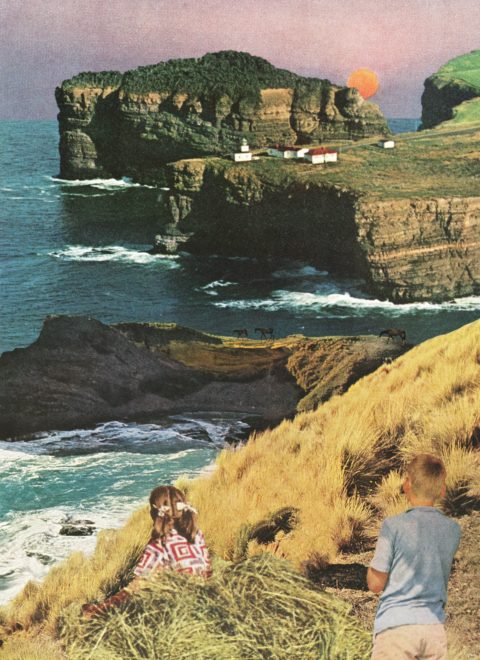

Only, I was on the other side of the fence around where the horses grazed. It was October, and the afternoon had turned hot. I’d lain down in the long, prickly hay to look at the sky over Bell Island, red streaked and amber and violet, getting dark already. I had felt the hard prickle of the dead grass sticking up through my heavy sweater—then I didn’t. Sometimes it’s important to remember the last sensation before it all goes away. I could smell a mineral tang that meant there might be frost that night. Things could turn like that. I had loved horses, but I was already forgetting that love.

There was a boy standing over me. A silhouette. I had to blink him out of the sunspots, squint to see him. His shadow was what woke me. He was a black shape with a pink fire all over his shoulders and down the sides of his arms and between his legs, because he stood at the top of the steep hill and the sun was out over the ocean but still high enough to hit him directly on the back—pow—eating at the edges of his hair, all the way down to his sneakers.

This was Antoine. I knew him—sort of. I’d seen him around. It’s hard to say what I knew.

He was a foster kid from Labrador, staying at the bungalow on the hill with all the rows of red earth where they grew cabbages. He didn’t belong there, but he didn’t seem to mind. It was clear he belonged somewhere. But everything he belonged to was a thousand miles away. I had never been more than 10 miles away from everything that mattered to me.

He got my phone number.

He got it because I gave it to him.

Antoine phoned for the first time a week later and asked me if I knew who it was I was talking to.

I said I didn’t know.

He asked me to guess. But I couldn’t guess, so he told me.

Then he called every day. He figured out when we had supper, and he called after that. He’d call and say hello and nothing else. There was nothing to say, but it was also impossible to get off the phone.

Sometimes I asked if he was still there. He would say that he was.

I was 12, and he was the same age—but I recognized that he was in love with me. The silence stirred me. It was hot and angry and tidal. And the stirring was new…or newish. But the silence could just as easily go flat—become boring. It was a matter of staying on the phone until the flatness twisted back into a foreign, physical longing that thumped through the receiver of the phone: mine for him, his for me.

All I knew was that I’d awakened and he was stretching to the sky and all around him the sun burned hard. I would picture that when I lay in the five o’clock darkness of October, upstairs on my mother’s side of my parents’ bed because I needed privacy.

They had dark blue wallpaper with a raised velveteen pattern. I touched it with my fingertips while we were on the phone, and sometimes it sent shivers. The bedspread was synthetic and shone in the gloaming of wanting to touch.