Why Are We so Obsessed With Cults Right Now?

And do the parallels with our real-life echo chambers have something to do with it?

As a child of the ’90s, I was first exposed to our collective train-wreck-like fascination with cults in the spring of 1997, when 39 members of Heaven’s Gate took their own lives in San Diego, believing it would get them onto an alien spacecraft. And growing up in Quebec, I’d often hear about the high-profile publicity stunts of Raelians, whose followers believe that life on earth was scientifically engineered by an extraterrestrial species named the Elohim. The free-love-minded Raelians would distribute condoms at the entrance to high schools, claim to have cloned the first full human being and organize internships that taught the fundamentals of a cosmic and orgasm-inducing meditation technique.

Having what’s arguably the world’s largest UFO-based religion in my own backyard—the Raelian movement set up its world embassy UFOland compound just outside Valcourt, Que.—made me wonder about the kinds of people who relinquish some of their critical-thinking faculties in the hopes of achieving a greater sense of purpose and belonging. Lawrence Wright, author of Going Clear: Scientology, Hollywood and the Prison of Belief, argues that all humans are vulnerable but cult adherents are particularly reliant on absolutes. “I’ve always been interested in religions and why people believe one idea rather than another,” he explains in the documentary based on his book. “I’ve studied Jonestown and radical Islam; there are often good-hearted people, idealistic but full of a kind of crushing certainty that eliminates doubt.”

“I’ve studied Jonestown and radical Islam; there are often good-hearted people, idealistic but full of a kind of crushing certainty that eliminates doubt.”

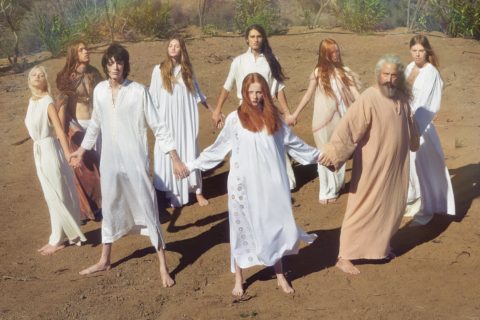

From the terrifying desert commune of the Manson Family to the spiritual rehabilitation of A-list celebs drawn to Scientology, pop culture has long been obsessed with the plight of those willing to blindly subscribe to a fringe ideology. And lately the topic of cults seems to be beckoning our attention at every turn, with Netflix’s much-talked-about true crime series Wild Wild Country, about the controversial Indian guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh; Hulu’s fictional cult drama The Path; “I Admit,” R. Kelly’s 19-minute R&B response to allegations that he ran a sex cult; and the impending high-profile trials of the members of NXIVM, another sex cult in upstate New York, now linked to Seagram heiress Clare Bronfman and Smallville actress Allison Mack. That’s without mentioning American Horror Story’s cult-themed seventh season and HBO’s Rapture-esque The Leftovers, which features Liv Tyler as part of a chain-smoking, blasé-looking all-white-clad cult known as the Guilty Remnant.

So why this sudden spike in cultish entertainment? Commenting on Wild Wild Country’s recent Emmy nods and broader cultural resonance, executive producer Mark Duplass told Deadline that he loves how viewers are able to identify with the series’s niche

religious movement, given that “nobody in this country is identifying with anyone right now who doesn’t believe exactly as they do.” And he has a point. The rapid polarization of political discourse in the United States and also abroad is making people less inclined to feel any empathy for those with differing world views and more likely to retreat even further into their extremist enclaves.

The rapid polarization of political discourse in the United States and also abroad is making people less inclined to feel any empathy for those with differing world views and more likely to retreat even further into their extremist enclaves.

Take, for instance, the viral video of a New York City lawyer threatening to call immigration on employees and customers for speaking Spanish at a Fresh Kitchen. Or that of a Black Lives Matter Toronto organizer calling Prime Minister Justin Trudeau a “white supremacist terrorist” at an anti-Islamophobia rally shortly after the Quebec City mosque attack. On the surface, these two news items couldn’t be more different: One shows an unwarranted tirade initiated by a racist client; the other, like-minded members of a community coming together to express their anger. Nevertheless, both seem symptomatic of what happens when people stop engaging in dialogue and resort to shouting matches. And, ultimately, could chanting mantras such as “Lock her up” at Republican rallies and gratuitously calling people out using immutable identity markers stand as modern iterations of cultlike behaviour? Wearing oversized capes and attending clandestine retreats in secluded forests might not be so popular in 2018, but punishing those whose perspectives are deemed heretical to a movement appears to be all the rage at both ends of the political spectrum.

Of course, the Trump cult is way scary. First and foremost because even fellow Republicans and the president’s own son seem to acknowledge he’s running a cult. Take Trump Jr.’s answer to Republican senator Bob Corker’s remark that the GOP is fast devolving into a cult: “If it’s a cult, it’s because they like what my father is doing.” When someone from Trump’s own party dares to contradict his version of reality—like when Senator Marco Rubio was chastised on Fox News for not following the president’s lead in recognizing the “talent” of North Korean dictator Kim Jong-un—you have to wonder how many other party members are holding back for fear of being excommunicated. As a head of state, when your supporters and the media outright reject any interpretation of reality that contradicts what you’ve said, you have to congratulate yourself for taking a page out of the cult playbook.

As a head of state, when your supporters and the media outright reject any interpretation of reality that contradicts what you’ve said, you have to congratulate yourself for taking a page out of the cult playbook.

While in no way comparable to the fear mongering and sheer verbal (if not outright physical) violence of the alt-right, the damage being done at the other end of the spectrum can also be pernicious. While it’s entirely justified to ban hate speech targeting marginalized groups, it’s quite another to discourage people from expressing ideas considered uncomfortable or unresolved. The dangers of groupthink apply to the left as well, and it has contributed to making Trump’s ascent so spectacular.

When controversial speakers such as British polemicist Milo Yiannopoulos are prevented from speaking at public events (thereby shutting down the possibility of challenging their short-sighted world views), when trigger warnings are issued at Cambridge University to flag “potentially distressing topics” in Shakespeare’s plays and when British broadcaster Cathy Newman spends a half-hour trying to shame Toronto psychology professor Jordan B. Peterson for his impassioned contempt of postmodernism instead of unpacking what he actually says, you realize just how contained the algorithmic bubbles we live in can be.

“In order to be able to think, you have to risk being offensive,” Peterson tells Newman when questioned about his right to offend. On that matter, I’m with him, as the opposite—censoring your ideas out of a fear that they may appear “divisive,” to borrow a word Newman repeatedly uses during the interview—might resemble something akin to The Handmaid’s Tale’s totalitarian Republic of Gilead.

Among the many markers of cultlike behaviour identified by the American Family Foundation, you’ll find leaders using guilt to control their members and an overarching “us versus them” mentality. Left- and right-wingers alike could be accused of such manipulative tactics. Peterson’s dismissal of anthropology and sociology classes as “indoctrination cults,” for instance, merely reinforces caricatures about left-wing activists instead of framing his critique in shades of grey. But it’s hard to rise above the current phenom of 24/7 preaching and online information cocoons, where followers chase enlightenment by binge-watching hours of content on YouTube or social media platforms that will conveniently validate their world views. That’s behind Peterson’s rapidly ascending popularity but also that of figureheads of much graver concern: conspiracy theorist Alex Jones’s InfoWars platform or even the sophisticated propaganda of ISIS—one of the most successful cults when it comes to online recruitment and self-radicalization.

It’s hard to rise above the current phenom of 24/7 preaching and online information cocoons, where followers chase enlightenment by binge-watching hours of content on YouTube or social media platforms that will conveniently validate their world views.

So what to make of our renewed interest in cults, and should we be concerned about the seemingly insurmountable divisions we face? I’m a firm believer in the power of the fifth estate to take gurus, spiritual leaders and assorted extremists to task on their most dubious claims. I’ll never forget when Rael—birth name Claude Vorilhon, self-described “gardener of our consciousness”—appeared on Quebec’s top-rated talk show Tout le monde en parle in 2004 with his topknot of hair to promote a Playboy spread featuring three topless females from his so-called Order of Angels.

The pull-no-punches TV panel picked apart the guru’s outlandish call to create a geniocracy as well as his boldfaced claim that he had used women’s wombs for cloning experiments. Once that TV appearance was over (it’s still regularly cited in media circles nearly 15 years later) and the man’s wonky assertions had been debunked, few people could claim with a straight face that they subscribed to Raelianism, and the movement eventually had to put its UFO compound up for sale. Think of it: A single entertainment talk show played a pivotal role in challenging the mind-manipulation techniques of a prominent international cult. I’m guessing that that media appearance didn’t help with its recruitment efforts.

As the first NXIVM trial gets underway and Trump continues to confound what many expect of world leaders in the 21st century, we have to remember to think critically about claims being made at either end of the political spectrum. In a world that seems like such a messy minefield, where the potential to be shamed or silenced for having an independent thought seems so great, we must remember to be courageous, speak up and, in the wise words of one great Canadian heartland rocker, keep on rockin’ in the free world.