This super-luxe cream was developed by monks in the Czech countryside

At first glance, the Czech countryside looks like something out of a Brothers Grimm fairy tale: deer caper through beds of lupine while wildflower-flecked fields lit gold under midsummer sunshine recline toward the Bohemian Forest—a primeval tangle of pines, glassy lakes and peat bogs. I half expect to encounter a tiny cottage and a septet of dwarves. Instead, I meet French monks in brown robes and hairnets emulsifying chamomile and beeswax. They’re making Fresh’s Crème Ancienne—a rich face cream inspired by a 2,000-year-old recipe. “Having this cream handmade in a monastery sounds like it was a commercial idea, a marketing gimmick, but it’s not,” says co-founder Lev Glazman. “We felt that in order to respect the story of this cream, it needed to be carried out in this way. And we were uncompromising about that.”

The monks proceed to fill white glass jars with the concoction, working in the kind of dense silence that makes sneezing feel rebellious. It’s the kind of quiet you need to travel an hour and a half outside of Prague, past hop fields and lavender-lashed meadows, to find.

There is something magical about this part of the world—Prague’s Romanesque buildings are washed in lickable shades of pistachio and lemon, as if each were carved out of macaron batter. Dubbed the City of a Hundred Spires, Prague is richly forested with Gothic cathedrals and their pointy peaks; at nightfall, the spires are lit, decorating the landscape like sparklers on a giant birthday cake. Fittingly, Fresh is celebrating its 25th birthday this year. The company’s inaugural products were vegetable-based oval soaps crafted in the south of France and scented with cyclamen, verbena and wisteria—each artfully wrapped, like presents, in craft paper and wire. “I thought the approach to beauty was too formulaic, too regimental,” says Glazman. “When we founded Fresh, I wanted to create something more emotional; something about passing down rituals through the centuries.”

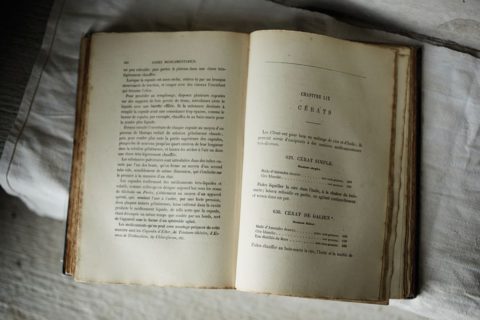

In concert with that approach, Crème Ancienne, which launched in 2003, uses a recipe that hails from the second century. The world’s first cold cream—made of beeswax, almond oil and rose water—was created by Greek physician Claudius Galen (doctor to Emperor Marcus Aurelius of Gladiator fame). Galen worked as the resident sports doctor at a gladiator school, treating the fighters’ wounds and burns after battle. (Legend has it that in Galen’s four years on duty, he lost only five patients.) Glazman discovered the formula in a 19th-century pharmacopoeia housed in the library at Fresh’s French laboratory. “I wanted to create a very rich and nourishing cream. Most people’s skin is very dehydrated, especially in wintertime. This cream fascinated me because it contains only 17 per cent water.” (Fresh products are known for the abundance of their marquee ingredients. The company’s honey mask, for instance, contains nearly 40 per cent honey—so much honey, in fact, that it wouldn’t be out of place on a breakfast tray.) Glazman only tweaked Galen’s original formula, using meadowfoam seed oil (instead of the greasier almond oil) and adding chamomile flower wax for its anti-inflammatory properties.

But if the product is simple, the logistics of having it handmade by French monks is not. “It would be impossible to make this cream in an industrial process. It must be handmade in small batches, like an artisanal bakery,” says Glazman. The brand sent letters to several large French abbeys, and a group of Norwegian nuns expressed interest in the enterprise. Seven nuns in Tautra, an island off the coast of Norway, handcrafted the cream’s inaugural batches. But the sisters couldn’t keep up with production. Glazman was then referred to this Czech monastery, which, incidentally, must be kept cloaked in a Bondian secrecy. (The monastery’s name, precise location and even its architect are not to be disclosed.) “When we arrived here for the first time, it couldn’t have been more fresh,” Glazman says with a small smile, taking pleasure in the pun. “This place was so pure.” He tells the story over lunch in the monastery; it’s a spread of toothsome vegetable soup (ingredients freshly picked that morning) and crusty bread. The setting—a long wooden table adorned with wishbone chairs and delicate field flowers poking out of mason jars—has all the rustic, monastic-chic qualities of a space styled by Kinfolk magazine. One of the brothers, who I’m told to refer to plainly as a monk, describes the meal differently: “It is prepared without any needless luxuries.”

Crème Ancienne (from $164 a jar), undoubtedly falls under the needless (if delightful) luxury category. “All of us monks wish to renounce the things that pass away in order to turn to the things that endure. Staying youthful is not of interest to us. Our sights are turned toward eternity,” says a monk. “We are learning to turn away from human beauty, which, like a flower, can fade in a single day.”

The silent manual labour involved in making the cream, a monk explains, allows them to pray and to support the running of the monastery. (When they’re not making cream, they whip up mustard and Nutella-like spreads.) But about the philosophical disjunction between a devotion to the eternal and the creme’s allegiance to youth and beauty, the monks remain silent. Some things, apparently, God only knows.