Is Work/Life Balance Really Possible? How to Avoid Unhealthy Career Mantras

A quick scan of the headlines from the past week paint a bleak picture of what it’s like to be a young worker in today’s job economy. Everyone from Mary Kate & Ashley’s Dualstar interns to ex-Amazon employees are revealing the long hours, meagre wages and mistreatment they’ve suffered in the name of success in their field. One 22-year-old even made headlines for living in a tent to afford his internship at the UN in Geneva. Although these stories are varied in their tales of desperation, they all demonstrate how a hungry desire to succeed at a fulfilling career often wins out over a desire for work/life balance and fair monetary contribution.

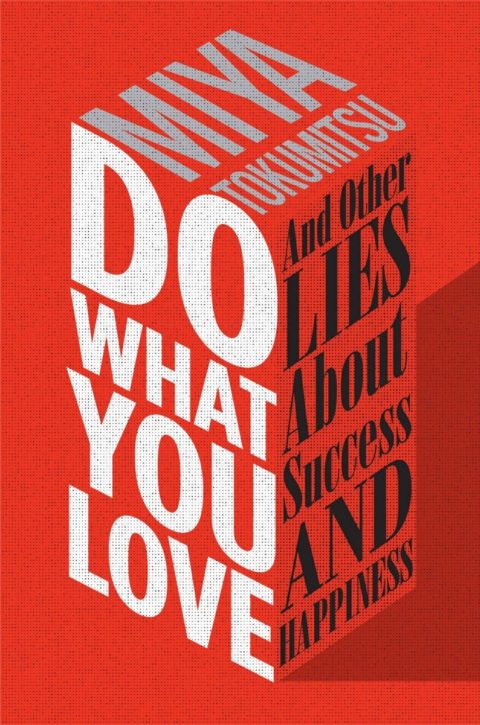

Miya Tokumitsu has a problem with this. A writer, contributing editor at Jacobin Magazine and author of the new book Do What You Love: And Other Lies About Success and Happiness, Tokumitsu takes issue with the much-advised aphorism “Choose a job you love, and you’ll never have to work a day in your life,” and feels that there’s a direct link between mistreatment of employees and the modern desire for the perfect, “loveable” job.

“Nothing makes exploitation go down easier than convincing workers that they are doing what they love,” she writes in the Slate piece that inspired her book. “Emotionally satisfying work is still work, and acknowledging it as such doesn’t undermine it in any way. Refusing to acknowledge it, on the other hand, opens the door to exploitation.”

Tokumitsu argues that idealizing your job as a “love” or extension of your identity changes the power dynamic between employee and employer. “The work becomes something done not for wages, but for pleasure and moral self-improvement,” she says. “Once that narrative takes hold, it becomes really hard to move the conversation back to the nuts and bolts discussion of wages and benefits. That whole discussion becomes crass.”

She cites statistics and circumstances of poor labour conditions that are undoubtedly familiar to any twenty-something getting their career off the ground, and easy to add to from current headlines: the 46% of the workforce who feel compelled to check email on sick days (50% of the workforce also do so on the weekends, 34% while on vacation), employees too afraid to clock their overtime hours, the dismal opportunities for maternity leave.

Her examples are furthered by the New York Times piece on the Amazon employee culture—one of the tenants of Amazon’s employee guide is “Frugality,” and its employees are reportedly encouraged to embrace spending as little as possible, covering “cellphone and travel expenses” themselves. One employee reports that he usually “worked 85 or more hours a week and rarely took a vacation.”

This Amazon exposé also reveals another point of Tokumitsu’s: that the Do What You Love mentality takes not just a financial toll on employees, but a mental one. Tokumitsu’s view, the two schools of thought at the root of Do What You Love are a) “a deeply entrenched sense of a work ethic—the idea that your work and your attitude towards it are expressions of your morality and character” and b) “the belief that your individual sense of self is extremely important.” Neither of these two beliefs sound particularly damaging–until you hear this extreme level of career attachment manifested in quotes from former Amazon employees.

“I was so addicted to wanting to be successful there,” says one ex-Amazonian. “For those of us who went to work there, it was like a drug that we could get self-worth from.”

“One time I didn’t sleep for four days straight,” says another. “These businesses were my babies, and I did whatever I could to make them successful.”

These words endorse Tokumitsu’s argument: when you view your job as not just your meal ticket, but an extension of yourself—your baby, even— the ups and downs, rough days at the office or disruption on your path to success are devastating, and it makes it difficult to see the forest through the trees.

While it is fine to strive for a job that is intellectually and financially rewarding, to lay all your hopes and needs on one position is to give your career—and your employer—too much power. What the headlines, Amazon story, and many of our own job trials should remind us is, as Tokumitsu writes in her book, that while “a fortunate few may find the actual tasks of their work to be a source of love…it is also everyone’s right to find love elsewhere.”

Or, in other words, if you’re living in a tent to afford your job, screw love and just find another gig.